Lagos Newbie

I had been angry for the past two weeks—angry at the world and myself, and second-guessing all my life decisions. It was hard not to transfer that frustration to Lucy, who shared office space with me. As I arranged files in the large drawer this morning, she snuck up behind me and covered my eyes with her palms.

“Guess who?” she asked.

Her Victoria's Secret perfume gave her away immediately.

"Lucy," I muttered, not in the mood for games.

She dropped her hands, walking around to face me, her eyes scanning me up and down. "Why do you look like this?"

"Girl, I can’t remember the last time I slept through the night."

"Mehn, have you talked to your neighbours? Maybe they’re going through the same thing?"

I shook my head. "No. I barely know them."

"Well, it wouldn’t hurt to ask. Just to see if they’re also having these weird experiences."

"I’m thinking of moving out," I admitted.

Lucy raised a brow. "And your rent? You think you’ll get it back?"

"I’ll ask the agent. If he won’t refund me, I’ll move back to my aunty’s."

"If you had told me you were getting a house in that area, I would have discouraged you."

"Nobody warned me."

"That agent will not make heaven," Lucy said, shaking her head. "He did you dirty because you’re a newbie. People who know Lagos avoid that area like the plague."

•••

A year before this conversation with Lucy, I got a job as a content marketer on Lagos Island and left Ibadan to move in with my aunty. Her house was a 45-minute drive from my office. Aunty Bolaji ran a large provision store in Ikeja and was successful by all standards. Despite family pressure after her second divorce, she decided not to remarry.

Family members had a lot to say about her.

“The money will never allow her to obey any man,” they said. “No man will marry a woman like her—flaunting her fancy cars, living like a queen in Lagos.”

“It is even her children I pity. Both from different fathers and without a father figure.”

But Mum was the only family member who had her back.

I had visited Aunty’s house a few times before moving in. It was like a second home. The large lawn stretched from one end of the fence to the other, and by the gate, a massive caucasian dog sat in its cage, watching everything. I vowed to stay clear of that dog.

After work, I would join Aunty in the kitchen to make dinner. My legs would tremble from exhaustion, but I wanted to prove I wasn’t a burden. Mum’s words echoed in my mind, “When you’re staying with someone who is not your mother, do not complain, just help.”

When Mum saw me off to the car park at Ibadan, she hammered it again: “Do whatever she asks you to do. I do not want any wahala.”

I would say things like, “I am not too tired, Aunty,” even when I was. I even convinced her to stop inviting the laundry man, wanting to be useful. “I can handle the laundry, and we can use the money for something else.”

Eventually, all the housework fell on me. I would wake up to prepare breakfast and come home to make dinner. One morning, after devotion, I mustered the courage to say, “Aunty, work is getting hectic. I might not be able to prepare dinner every day.”

She nodded absentmindedly, twisting the ends of her braids. “Don’t forget your keys when you leave for work. I won’t be home early today.”

That was it. No argument, no guilt trip.

I dragged myself home after a long day at work. As I neared Aunty’s street, I checked my phone and saw 15 missed calls from Mom. I called back immediately.

“Joke,” she fumed, “what is this I’m hearing about you? I told you to behave yourself!”

Aunty Bolaji told Mum she did not send her children to a boarding school to be weaning an adult like me.

That night, I knew I needed to take a step. Over the next few weeks, I was determined to rent my place.

One evening, after work, I boarded a bus to Tinubu from Balogun. The plan was simple: move out of Aunty’s house without informing her or Mum. I could blame my decision on the cost of transport to work.

I visited almost every corner of Lagos with different house agents. One of them took me to an apartment with a flooded drainage system: the house, a floating mass of water.

“Sister, see how cool this house is in this hot Lagos. You don’t even need an AC!” he grinned.

I stared at him in disgust and left without saying a word.

Days later, I alighted from the bus, and as I walked down an unfamiliar road, I checked Google Maps. I had lost my way. The agent’s directions had not helped much, and I did not want to call him—he would probably laugh at me.

I asked a passerby for help, and a man in his mid-thirties offered to show me the way. “Follow me, fine sister,” he said, complimenting my outfit and hair as it bounced in mini-twists.

On the busy streets of Lagos, random people often complimented my hair. Some passengers in public transport asked if they could touch it and what products I had been using on it. I followed slowly, wary of all the warnings I had heard about Lagos.

After a few minutes, he pointed to a bus stop. “Sister, this is where you’ll catch a bus for ₦100. Don’t let them cheat you o.”

I thanked him and started toward the bus stop.

“Erm, sister, do me something now?” he called after me.

I dug into my purse and handed him ₦200.

“Ah, sister, this is too small o. I have children your age,” he protested.

I kept walking to catch the bus, ignoring his pleas.

It was August, and the rain had not stopped for days—little showers here and there. I hoped it would stop before I reached my destination, but the rain only got heavier as we approached the last bus stop.

The driver honked impatiently. "Aunty, abeg, comot my bus. You be salt?"

I stretched my hand out of the window to check how hard the rain was falling.

The driver kept honking. “Aunty, abeg now! No turn my bus to your house.”

I sighed and stepped out, bracing myself for the downpour.

2.

The new house agent I found was waiting under a nearby kiosk. As soon as he saw me, he waved, “Sister, I don dey wait for you since. You no dey check phone.”

I rummaged through my handbag and brought out my phone to find ten missed calls from him. “Oga, I dey inside bus and rain dey fall, I no hear wen the phone dey ring.”

He gave a performative sigh, “No wahala sha. As you don delay me, you go add something to the agent fee. I get other places I won see today but you don spoil my plan.”

I stared at him, the dampness from the rain seeping into my clothes. “You wan waka inside rain?”

“Aunty, I no like this kain thing o. Ehn.” He grumbled, shuffling towards the building. “Make we enter.”

The house was a new, freshly painted building tucked behind the kiosk. It had a cosy ambience, the kind where neighbours seemed to mind their business. It was perfect for me; I liked it. When we got to the door, a woman holding a shopping bag came out of the house. She exchanged pleasantries with the agent, who introduced her as the housekeeper.

“She dey clean the house and she fit run small small errands for una. Just tip her. Nah my Uncle’s sister she be. Good woman,” he said and gave me a reassuring nod.

I felt relieved.

He kept rambling about how I would enjoy living in the house.

“You are lucky o. This room na brand new. No bad energy in your space. At this point, I dey envy you sef,” he said and grinned.

I could not hold back my smile, either. I loved the house. It looked clean and well-kept, with every corner spotless, and I felt at peace.

The apartment was fully furnished and I only moved in with my luggage. On Saturdays, I played music through my speaker and danced alone. I tried new recipes and tended to the new set of plants I got from the horticulturist down the street. For the first time in a while, I felt at peace with my existence—this space made me forget Lagos chaos—my house was peacefully tucked away from the rest of the world. But the little unsettling things began.

It started with faint sounds—like the house creaking, plates shuffling in the rack or a slight knock on my door—like someone unsure of the occupant they came to visit. “It is not important,” I reassured myself. These things are bound to happen. Houses expand during the day and contract at night because of the heat from the sun.

After a cold shower on a Friday evening, I was in bed contemplating whether to sleep or binge-watch a new horror series. Then, I heard a faint thud from the kitchen. Another sound came again, like the clattering of plates and spoons, as if someone was looking through the cutlery and plates to select one that suited them.

“It might be rats,” I told myself, although I had not seen any since I moved in. When I peeped into the kitchen, everywhere was still.

Another evening, I got home from work tired and ready to collapse into bed. But I needed to use the toilet first. As I entered, I noticed little insects crawling up the tiled wall. I moved closer and watched them march in eerie synchrony. Then, they melted into the wall.

My heart skipped a beat. I had been planning to get blue light glasses because I spent long hours staring at the screen, and my sight might be deteriorating. But when the hair on my arms rose as I stepped out and the door slammed shut with a force that made me jump, I knew it was not my sight.

My body went numb, every nerve telling me to flee. Instead, I stumbled towards my bedside table, grabbed my bible and held it close to my chest, feeling its cool leather on my palms. The goose bumps on my skin disappeared but not the unsettling feeling.

A few weeks passed without incident—until a Saturday night, exactly three months after living in my new space. I had dozed off watching a horror series when I jolted out of sleep around 2 in the morning. The room was dark except for a faint light coming in through the window I had left open and a cold breeze slipped in, slitting my skin like shards of glass. I shuddered and pulled my knees to my chest.

The scented candle I left to burn on the table flickered widely as if fighting to stay alive. Then, I heard the first sound. A bang echoed from the kitchen and my heart skipped a beat. The cabinet door slammed shut on its own and I heard the loud clatter of my pots and pans.

I sat up and tried rationalising it. The neighbour next door prepared her food late at night when she returned from work, but this was different. I had seen her moving her travel box into an Uber earlier that day because she spent her weekends with her family in Osogbo. A chill ran down my spine—the sound was indeed coming from my kitchen.

Suddenly, something caught my eye—a black, sleek cat with glowing eyes zooming past my window. Its claws scratched the window pane, and its meow reverberated after it disappeared into the night. Cats on Lagos streets are common, but this one seemed different. It moved with an unnatural elegance, circling the house as if stalking something.

For the remaining hours of the night, I sat on the edge of the bed, gripping my bible so tightly that it left marks on my palms. My teeth clattered as I muttered all the bible verses I could remember. I prayed for protection against what might be lurking in the house.

Mum’s stern voice resounded in my mind, her words laced with distaste. “I didn’t support you moving out in the first place. Now look at what you’ve gotten yourself into.” She would blame me for this—blame my stubbornness, blame the restless spirits that seemed to follow me.

She would also talk about the dead, how the bones of my dead father would be turning in the grave for leaving the safety of Aunty’s home.

•••

Long before the strange movements each night, before I started hearing objects crawl inside the ceiling, before I woke up to an unnerving puddle of blood at my doorstep, and before items began to disappear one by one in my room, I got subtle signs.

The first was when I went to fetch water from the well, the few times the plumbing had an issue. As I laid down the bucket, a long strand of jet-black hair caught my gaze, it was drifting on the surface. I overlooked it. Perhaps it fell from someone who used the well earlier. But the second time I went to fetch water, I found more strands of hair. They were not floating on the surface. They were clumped up around the bucket. I got a sickening feeling in my stomach and the air around the well became still as if the breeze itself was trying not to breathe.

The day I told Lucy about the eerie happenings in the house, she gave me a knowing look.

“That should have given you all the hint,” she stated, tapping her finger on the table.

Then she told me what I hoped was not true—the house I rented was built on land that used to be a cemetery.

That Saturday, I woke up and packed a little suitcase. When I told Lucy about my plan to go to my aunty’s place, pretending I only came over for a casual visit. She laughed at me.

“I still have the house keys,” I said.

If I came out plain, I knew Aunty would say, “I thought you are all grown up now and you can make decisions for yourself?”

But as I sat at the edge of the bed, something nagged me. What if it was the horror movies I had been watching? I was hesitant as I stared at my packed bag, then dropped it. I sat on the bed and decided to ditch the late-night horror movies that had been messing with my mind.

To calm myself down, I went into the kitchen and prepared a pot of Jollof Spaghetti—I was convinced I had finally found the source of my ordeal. “No more horror movies.”

In my dream, shadows lurked at the corners of my room that night. The windows and doors slammed shut and opened again as if an invisible force were trying to get in. Then, my bed lifted from the ground and floated in space. I woke sweaty, expecting to see the chaotic room, but everywhere was still. The neighbour’s generator worked undisturbed, and my rechargeable fan swirled slowly. Everywhere was quiet—very quiet.

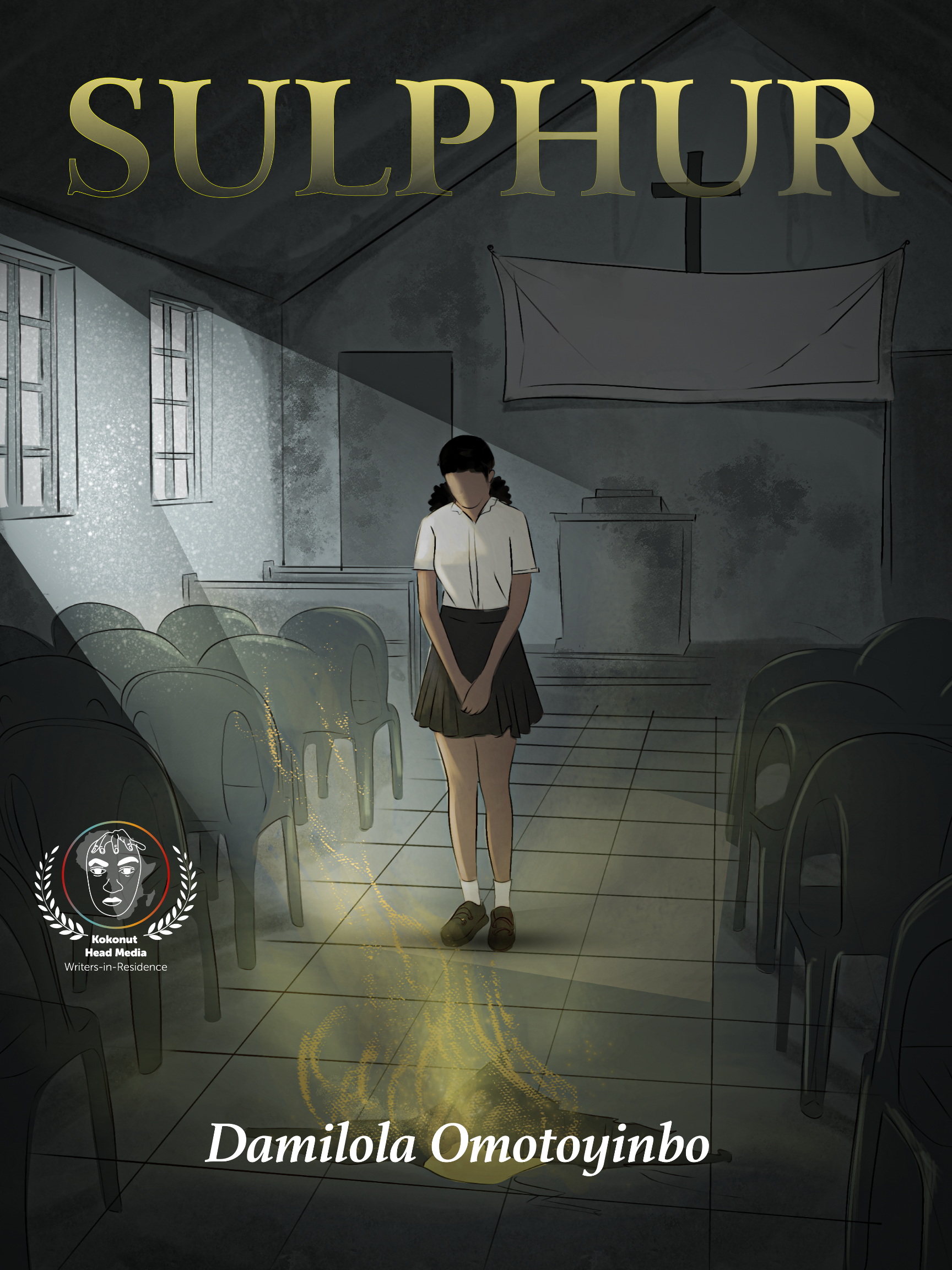

I adjusted in bed. The room was warm despite the swirling fan. I shifted again, and my head sank deep into the pillow. My scalp itched, and I started to scratch it, but something was amiss. My fingers brushed clean skin. My mouth fell open, and my heart raced. I moved my palms over my head again, but my scalp was still smooth and cold. There was no kinky hair, no mini-twists.

My whole body began to itch and I felt an invisible force pressing me down. I stood up from the bed but my trembling palms did not leave my scalp. My gaze moved to different sides of the room, then it rested on the bedside table. There it sat, my 4C hair in a little heap—shaved clean from my scalp.