Blue Ruins

If you ask Ahachi the colour of love, she would say blue. Blue, because on that dewy morning at Ndibe Beach in Ehugbo, her blue nylon bonnet sank deep into the ocean, and she swam her farthest to rescue it. Blue—because when she resurfaced clutching her blue bonnet, a man with permed black hair sat on the shore, his smile revealing a row of gleaming white teeth. His clothes were glued to his body, and his net was full of fish. He must be new, Ahachi wondered. She knew all the fishermen, at least by face, but something about the man standing before her was strange. When a fisherman was wet, the wetness was obvious; It was water on a man, separate, drenching, not this glistening and near-shiny drip that adorned this man’s body in the name of wetness. Ahachi and this man locked eyes for what felt like an eternity before he broke the silence.

“My name is Nkasi,” he said, stretching his hand for a handshake.

He was cordial. He did not want her to run away at the sight of him moving or circling her with so much fluidity and excitement. Were she a water woman, he would have greeted her differently. In the water world, pleasantries were signalled by splashing—a rhythmic and continuous dance-like gurgling meant to show warmth and familiarity, but he was sure it would scare her, so he stuck to a simple handshake. Ahachi was panting, not just from the strain of her swim but from the mysterious dilation of his pupils when he shook her. His palms had a current, like electricity, and Ahachi knew from then that their exchange was more than a mundane handshake.

That evening, Nkasi wore a blue kaftan embroidered with shells and seaweed. Ahachi found herself admiring the art on his garment so intensely that she reached out, almost compelled to touch the fabric and feel its texture. Just as her fingers brushed against his hand, he began speaking again. She watched his mouth move, uneasy, yet excited that he let her touch him. He indulged her in a way no one else in Ehugbo had and he was handsome, so handsome, she concluded he was not of her world.

“You are the most beautiful woman I have ever seen, as fine as the ocean,” he said, stroking her arms.

“Thank you,” She managed to say, shifting her eyes away from his face and into the ocean.

“What is a goddess like you doing on land.’’

Ahachi Scoffed.

“What do you mean? Where else should I be?”

“In a beautiful otherworld with me,” Nkasi said, laughing like he had just made a joke. Ahachi laughed too because he laughed, not because she understood what his laughter was about. What other worlds existed for the living aside from the kingdom of death?

There were many rumours about Ahachi in Ehugbo, her village. She was seen as delusional by many, destitute to others, a nomad to some and to the few fishermen and market women she conversed with; she was a skilled swimmer, well on her way to madness. They believed she was not completely normal but enjoyed chatting with her, picking her scattered brain about seafood or trees. She knew the nature around her well. A fish seller once said Ahachi’s Moringa prescription cured her high blood pressure. Another said Ahachi asked her to apply coconut palm on her skin, and she has glowed ever since. They examined her advice with doubt and tried it as a last resort, and when it worked, they never thanked her personally, they just murmured their surprise and gratitude among themselves, never acknowledging her beyond banter. But Nkasi was different; something about him acknowledged her.

“What is your world like?” Ahachi asked.

“It is like paradise.”

“Really!”

“Yes, there are pearls and food, and it is clean.”

“Am I allowed to visit?”

“You’ve been very close to our borders.”

“Me?”

“Yes, you!” Nkasi said, splashing water on Nkasi as the waves approached them. She giggled and did the same for him, and that was how her relations with Nkasi began.

Nkasi was not fine in the way men were known to be fine in Ehugbo, with their big arms, yam-tuber legs, and goatee beards. Instead, he had a smooth, shiny face, long legs, and a torso that appeared elastic when he moved. Their newfound relationship was as fast as a flood, taking over the streets, sudden, relentless, engulfing. Nkasi came up to see her and remained at the shore. Water people like him could never leave the land at the sea's edge for long because their bodies would shrivel up and die. But he took the risk. He had never seen a land person swim as deep as Ahachi swam that evening to find her blue bonnet. Ahachi had sold seashells for weeks to raise money for that bonnet. The girls in Ehugbo wore it to protect their hair from breaking or simply for show, and she wanted to belong. When that satin bonnet began to sink, she chased it into the ocean and shook Ahachi’s world with her presence. When things fell that deep, land people left them, but Ahachi secured her bonnet and swam up to the surface like it was nothing. Land people who reached that depth drowned, their lungs betraying them in the crushing embrace of the sea. Nkasi and his water people witnessed Ahachi dive perfectly into their home; they watched her float from a distance, her movements deliberate, almost unearthly. She did not flail or gasp like others—they wondered what manner of land person she was, one who carried the sea in her spirit.

Nkasi fell in love with her boldness and went up to see for himself, falling even more in love. He wanted to bring her to his world, where everything glistened, and there was green; he wanted her to witness his realm of vibrant colours, gentle motions, and surreal landscapes; he wanted her to see this world where sunlight filtered through the water, where there were strange and beautiful creatures like turtles, sea snakes, and crabs, He wanted to show Ahachi what happened in the school of fish. Her kind of endurance was otherworldly, unfathomable for a mere human, and he needed her to see. Ahachi was not dumb, but somehow she thought Nkasi spoke about his home in parables, that maybe there was a part of Ehugbo near water, perhaps another beach, where houses were built atop the water, and none knew apart from Nkasi and his people, she did not ever think, Nkasi was talking about the deep end or the bottom of the ocean, did not know that Nkasi was for her eyes only.

The fishermen, boat riders, tourists, and villagers branded Ahachi as the mad orphan girl who spoke to the water. Ahachi, who was born by the ocean bed and left for dead, raised herself. She fed on fish, crabs, and dulce. She could read the waves the way she read the weather. She lived in Ndibe, in a small shed she built for herself with sticks and water leaves. She preferred the modest, low life the beach afforded her. She did not take work in Ndibe or agree to follow anyone home to do chores for a fee like other people did to make ends meet. Ahachi fed on whatever the ocean gave her: fish, weed, water. Ahachi, like a normal human being, could sell whatever value she gathered from the sea, but she didn’t. She believed in doing goodwill, in feeding street people with her roasted food. They were like her, either homeless or wandering about.

If anyone asked most people in Ndibe to gather all the mad people and send them packing, most people would come looking for her. More so now that she claimed a handsome man named Nkasi was courting her. Ahachi believed their envy blinded them. The beach was many things to many people in Ehugbo. For some, it was an escape, a place for a picnic, for relaxation. For others, it was regular. There was nothing special about the expanse of land, water, and trees that abounded. For tourists, it was a sight to behold. To the youth—boys and girls in Ehugbo—the mangroves and tall palms were a haven to explore their lust and desires. They were unashamed in how they held hands, kissed, popped bottles, took pictures, and locked bodies. She loved it for them and smiled when her eyes met theirs, catching them in the middle of their foreplay. This kind of play brought more children, and Ahachi wanted to play like that. Maybe one day, she would birth another human being just like her. A small person she would nurture and teach her diving skills. A little person who would inherit her long hair, breath control, and love her without question.

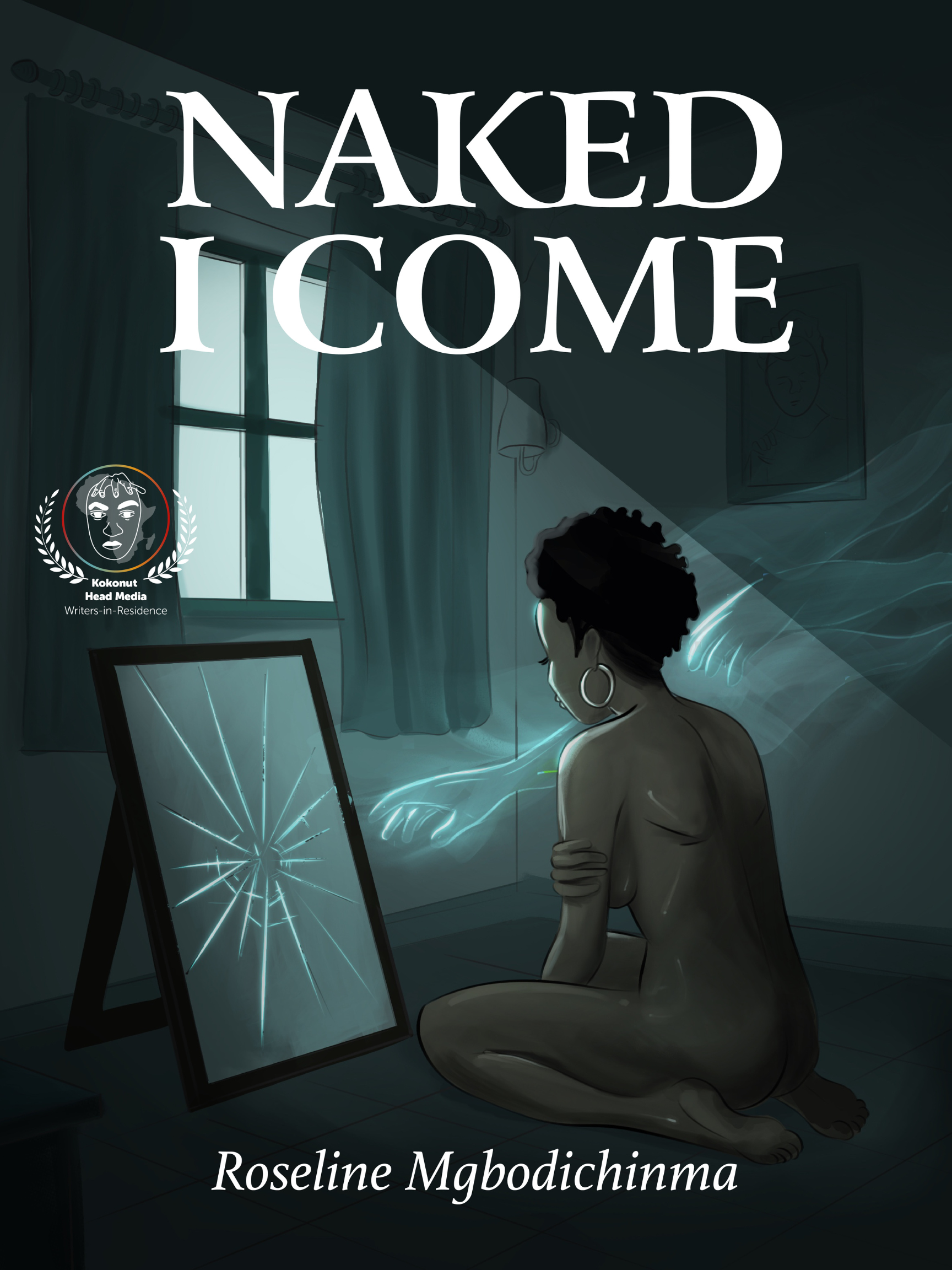

The first time Nkasi touched Ahachi like boys touched girls, she nearly lost her senses. Her body lit up in shivers as he grabbed her waist, held her face close to his lips, cupped her pointy chest, and almost went under her dress. It felt like swimming, but this time, his touch was water, and her breath was the movement. Ahachi was as breathless as she had been underwater that day when she chased her blue bonnet. As Nkasi reached the depths of her womanhood, she gasped. That evening, he caressed her to the sound of waves, katydids, and crickets. It was bliss. Ahachi saw stars without looking at the sky. The next day, Ahachi wanted to tell the universe about the heaven she had experienced. The attention felt too good to be hidden, she needed to testify. Nkasi touched her, and she believed she was perfect, like she finally belonged, as she had partaken in some grand human experience. She looked at everyone in a shyly suspicious way. If their partners touched them the way Nkasi did her, she did not understand why anybody would fight or why the world was bad. There had been instances where a wife yelled at her husband or a husband beat his wife in the middle of a family get-together. She did not understand it or imagine that it was possible for her to ever disagree with Nkasi—not after this magic he’d shown her body.

Ahachi only spoke to a handful of fishermen and women who caught and sold fish at Ndibe.

“A boy is chasing me. He is fine like a god.”

“Which boy will chase you with this your scattered look?” Madam Titus, a fish seller, retorted, sizing Ahachi up and down.

“I’m not playing. He touched me.”

“This everyday swimming has made you mad,” Madam Titus said, pointing at Ahachi and inviting her fellow fish sellers to come and see.

“Water don full her brain,” another fish seller yelled, and they all burst into laughter.

“Invisible man dey touch you every evening. This girl don finally craze,” Madam Titus added.

“I saw her laughing and catching wind yesterday evening,” Abasi, the fisherman, said, saddling his canoe while getting ready for his night fishing. He was a bestseller who caught fish at night, big and fresh, and by noon, all of them were sold out.

“No, I was hugging my Nkasi; he was there yesterday!”

“If you insist,” Abasi laughed.

Ahachi stood in their midst, confused and annoyed. If this sweet thing she had with Nkasi was madness, she was stark raving mad. Most of the women continued bagging their fish and laughing at her; some looked at her with so much pity.

“This one don jam Mami Water,” one of the boat drivers said jokingly.

“No be Mami Water. He is a person, but e dey live for water!” Ahachi yelled.

They did not believe her, and she hated it.

“This girl is the same age as my daughter, who just married a rich man in Cross River,” one seller boasted.

“My own daughter who is in the Polytechnic is about her age,” another said.

Ahachi simply walked away.

That evening, Nkasi visited again, but this time, he came with a request. He wanted Ahachi to follow him, to come and experience his world, but when he touched her, she was stiff, her body unwilling to play like it used to. What use is a love that everybody doubted? She began to see Nkasi with new eyes. Was he a person? Was he a spirit? And if she followed him to this world he spoke of, would she return to Ndibe Beach with breath in her lungs? Nkasi spent the evening telling Ahachi that he would not let her drown in the ocean, that they would go on adventures, that they would pick pearls, and he would show her the silly things land people like her threw into the deep and let go—scraps, bottle caps, hairpins, gadgets, and even food. To Nkasi, love was about choosing finer worlds, and the land was not as beautiful as the blue ocean. He wanted one night to show Ahachi how water people lived and how she could practice living underwater. It had never been done before, but she could break the cycle—teach land people that if they endured and swam deep into the ocean, there was a better world where they could love water people. They were not mermaids with fishtails but people with legs, limbs, eyes, noses, and ears; what was different was what was inside.

Nkasi and the people in his world lived very long lives. Their diving reflexes were excellent, their minds expansive, their blood vessels narrow, and their spleens contracted. Nkasi believed Ahachi had some of these features.

“Just one night.”

“I no fit, Nkasi.”

“But I love you!” Nkasi yelled. He was getting impatient. Land people did not know as much as water people. If he forced Ahachi into the deep, she would change her mind when she saw all the beauty. Nkasi’s eyes became deep blue and hollow.

“I leave my world to talk to you, and you cannot come with me?” He was now holding her firmly, his grip wet and sticky.

“You hold me too tight,” Ahachi begged.

“You think it is easy to be above the water all the time?”

“Nkasi, please!” Ahachi was begging. She saw the sudden rage in Nkasi’s eyes and began to shout. She was screaming from her guts, truly she don jam Mami Water.

Nobody was coming to her aid.

Abasi was a night fisher but showed up whenever his spirit led. He claimed that the ocean whispered to him when it was sure the night’s catch would favour him and no bad spirit would harm him. If he were there, Ahachi was certain he would have come out to save her already, or was he afraid? In Ehugbo, strange things happened at night. A cry could be a trap. People disappeared in the night because they came out to check out the noise in their backyard, how much more the ocean, where sacrifices were made, and people drowned mysteriously.

“My people say they would like to see the love of my life. I have to take you,” Nkasi said, almost begging but not loosening his grip on Ahachi.

“No land person has ever reached our world like you.”

“It was a mistake,” Ahachi said, sobbing. “I no go swim reach your side again.”

Nkasi did not understand Ahachi's resistance. He swore Ahachi was one with the water. When she swam, she held her breath underwater for long hours. On one of his many visits, he raced her, and they swam together. Her backstrokes were precise, nothing like any land person Nkasi had ever seen. He was simply urging her to dig deeper. He did not find the women in his world attractive—they were too much like him, too full of themselves, with a body and soul just like his. He wanted something different, something almost ordinary.

“You are special, Ahachi.”

“Biko, Nkasi. I go die.”

“I want you with me. Six feet under, you will live!”

Nkasi was tired of waiting for consent. He held her firmly and was ready to jump into the deep end. Although Ahachi lived by the ocean, keeping herself afloat was how she knew how to live. The land was her life. She learned to write on sand and perched on the walls of village classrooms to learn how to speak small English. She made clothes from land trees and brown algae, made buttons from stones, and sold them with seashells. Ahachi’s life was about keeping herself adrift. She was fluid with the water and firm on land and did not trust Nkasi to bring her back to land.

Men in love were selfish. In Ehugbo, men married women, and the women were never allowed to go back to their villages. They kept the women for themselves, and Ahachi was sure Nkasi would do the same with her underwater. A man was a man, on land and in the water.

Nkasi held Ahachi’s waist firmly against the tides, his arms firmer than moments before. He looked her in the eye and spoke like his heart was about to leave his body.

“You will come! You will say yes.”

The more Ahachi resisted, the more Nkasi's grip tightened. Nkasi had dragged her to the middle of the ocean, where the waters were deep. Ahachi was tired, out of breath, and no longer fighting Nkasi.

“Ahachi, do you love me?” he asked, still holding her.

“No!” she said almost silently.

Nkasi was furious. He held Ahachi's hands to her back and began pulling her legs. Whether she loved him or not, he was taking her to his world. Their heads were no longer above water, and Ahachi was struggling. Nkasi had more power, but she was fighting for her life, resisting as he tried to swim farther into the ocean. There were ripples in the water, like a big catch was rising to the surface.

“Big Fish!” Abasi screamed out from the bushes nearby. He put his hook into the water, and it caught Ahachi's dress.

“This one is heavy,” Abasi yelled. He was determined to catch and sell whatever was causing this much noise in the ocean. He spent minutes drawing his line, pulling and pulling, wondering what was holding his catch from rising to the surface.

Nkasi kept trying to swim deeper, wondering what was tugging at Ahachi’s dress. Ahachi was quiet in his arms, her arms unable to flail. Her head tilted backwards, her eyes closed, and her body stiff.