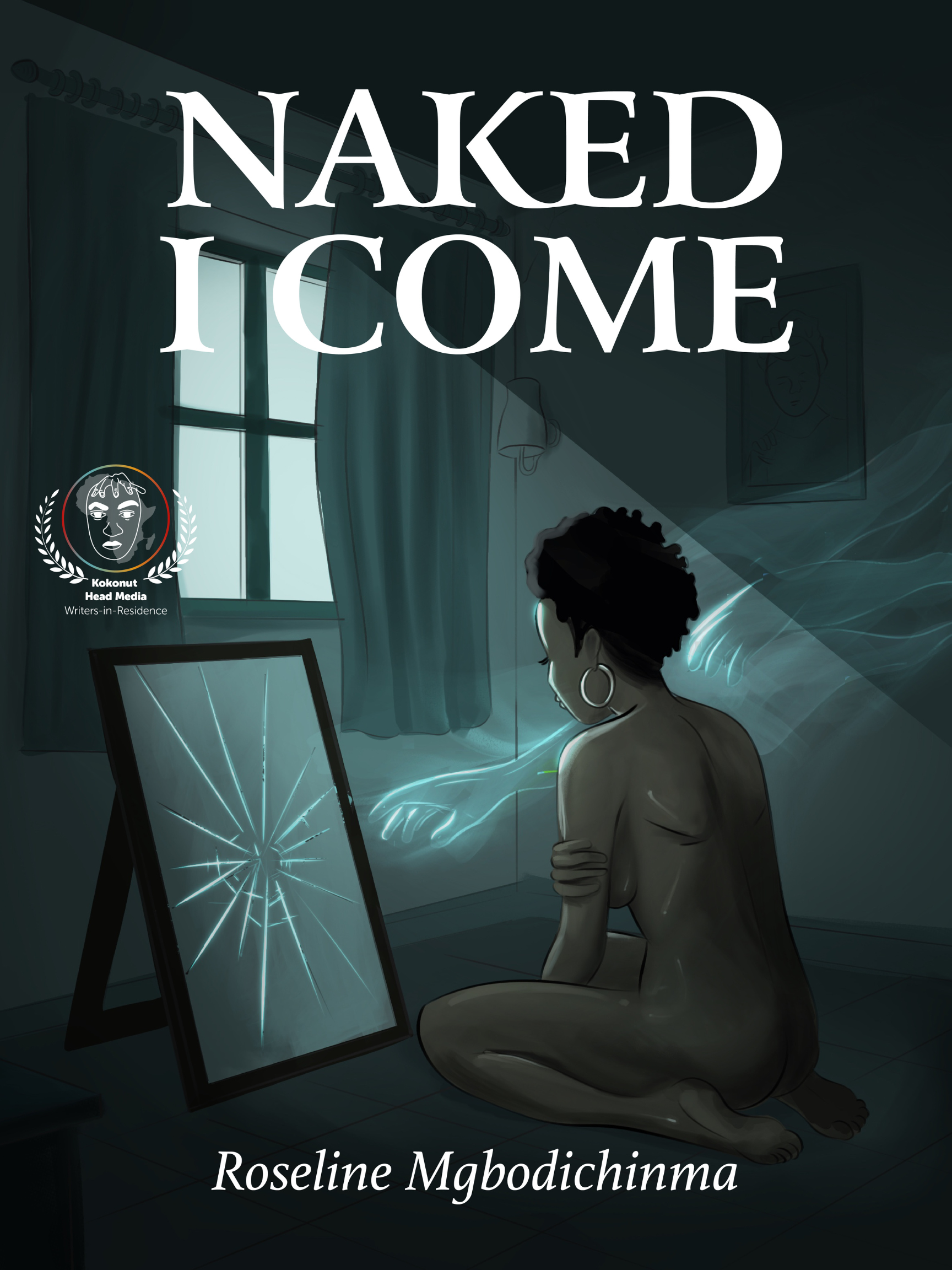

Naked I Come

The Start

The first time Azuka had an episode, it was considered a mild distortion, a racking of the brain. The stress and failed expectations in this country could make anybody lose a few seconds of sanity. It was not unheard of for a woman to be found roaming the streets and stomping her feet.

A passerby dialled ‘Big Sister’ on Azuka’s phone to inform the receiver that someone who belonged to them had just lost consciousness of the world. She had just started dancing and taking off her clothes outside a boutique in the heart of town and scattered her belongings abroad.

Nnedi boarded a plane from Enugu and yanked her sister off the busy streets of Port Harcourt into the nearest psychiatric hospital. Azuka paced breathlessly in the Psych ward, wondering how this had begun. Nothing was traceable.

The psychiatrist told Nnedi not to worry– her sister's condition was not uncommon– many politicians and big men were also his patients. They came in, got the country’s best treatment, and returned to business. It would be as though they had not tried to run and roam the streets moments before.

“All she needs to do is stop worrying, take her medications, and it will never get this bad again,” the psychiatrist assured.

He spoke as though humans were in control of their reflexes. How would Azuka put a pause to the voices in her head? Her thoughts had receipts for every day she spent failing at something. The spiralling in her mind was true. She was an unmarried thirty-eight-year-old with an unstable source of income and two abortions.

As they signed the discharge papers, Nnedi tried to convince her sister to return home with her and start afresh.

"You can even get your own apartment if you don’t want to live with me and my family,’’ Nnedi said calmly.

Azuka did not look at her or mutter a word. She just walked to the door silently. She simply was not having it. Her silence meant that Nnedi would spend one week nursing Azuka back to health before going back to regular programming. She was a civil servant prone to receiving queries; Azuka would not be the cause of her dismissal.

The Hook

Azuka stopped taking her medication. She declared Bible verses instead, bathing in holy water, anointing herself in olive oil, and drying out her body with mantles. She was at the front row of every crusade in town; her cable subscription only had channels like Adonai Worship and Emmanuel TV. Her kitchen stove and gas cooker were plastered in posters with numerous verses and themes inscribed on them – I am a champion, and my enemies must gnash their teeth in penury were among other “dangerous prophecies,” as Azuka called them.

Nnedi offered to send money for her to purchase her medication, but Azuka refused. When Nnedi pushed further, Azuka shouted into the receiver and slammed her phone against the wall. They went months without speaking to each other. Then, the madness struck again.

It became an annual occurrence. Some months of quiet, then a phone call that would send Nnedi crying into a luxurious bus or an aeroplane, depending on the size of her pocket.

It was always a dramatic reunion. Azuka would say hurtful things to her sister, and the nurses would shut her up with shots of Diazepam and handcuffs. It infuriated her, but she fell like a log heavy with rain in split seconds.

It was not long after one of her recoveries that Azuka brought a man home. She met Obichi on Facebook and decided to tie the knot after many chats and midnight calls. Nnedi begged her to rethink her decision or court the man a little longer, but she refused. She insisted on getting married to him before the end of the month. After all pushback failed, they had the most untraditional wedding. There was no money to buy a quarter of the items listed in the bride price. Bottled water and garden eggs without the customary Ose-Oji were served at the introduction. When it was time to shower the mother of the bride with gifts– Nnedi would assume this role since their mother died when they were toddlers– Azuka's husband bought a one-litre box of Hollandia Yoghurt, and sprayed wads of mint ten naira notes, 1,200 Naira in total.

All in all, Nnedi was relieved that Azuka would find a new manager for her episodes. She did not tell Obichi about Azuka’s medical records. She refused to be burdened by it. She did not pay Azuka’s hospital bills all these years, only to be saddled with the responsibility of teaching her and her new man how to get acquainted with each other’s histories and backgrounds.

Whenever Nnedi held devotions with her family, she made all her children say a thirty-minute prayer for Azuka, asking God to give her peace in the arms of this man they knew nothing about. It was one morning, while the family was binding and casting, that Obichi flooded Nnedi’s phone with nonstop phone calls. It was disrespectful to the Almighty to pick up calls during prayer. Nnedi put her phone on mute, and after she shared the grace with her children and husband, she attended to the influx of text notifications.

Nnedi, call me back. Why is your sister removing her clothes?

This has never happened before.

I am bringing her back to you now!’

Nnedi stared blankly at her phone screen. She was upset by his audacity. He boldly declared Azuka as 'your sister' instead of 'my wife.' Had he not rushed to marry her? What was this dissociation he was claiming?

She calmed herself, snapped her fingers three times over her head, and spat on the floor before texting him back.

If you leave now, you should be here before nightfall. Take the back seat if you take a bus. Pay for the remaining seats beside Azuka.

She texted like everything was foreign to her, as though she was utterly dismayed by the situation. She, who had studied Azuka like a book, understood her breathing patterns and mood swings. She was familiar with her slouches; period cramps caused her to bend to the side. The stiff curving of her back and her often twisted gait were the aftermath of willful foetus removal. Nnedi knew which one was which. She never asked. She just knew.

The Heat

She knew the abortions were for Farouk, Azuka’s ex-boyfriend in Kano. He was the one who told her he was waiting for the perfect time to start a family, the one who insisted she must terminate the pregnancy or risk losing their relationship. He was the same one who introduced Azuka to his family as his wife-to-be, the one whose parents welcomed her and asked if she had already gotten acquainted with Farouk's other wives. Farouk masked marriage well in his signature skinny jeans, face cap, and shy smile. He was Christian too, the type, according to him, that followed his God-given instincts over scriptures written by men with their censored outlooks on life. Azuka walked out of his life and never looked back except when her pastor said, "Pray for the downfall of your enemies. Let them die by fire." Those times, she closed her eyes and pictured Farouk drowning in the Red Sea.

Obichi called at intervals to express his distress during the journey. His voice was watery on the phone. Nnedi became irritated and retorted in a veale voice that did not hide her disgust.

"Obichi! When her mouth is dry, find Oral drip and give her. When she starts throwing tantrums, tie her hands or shove Lexotan down her throat. Explain to the other passengers, they will understand.’’

And they understood. The bus ride was laced with stories of mental disorders and plausible solutions.

"Just spend 21 days on the mountain and her brain will reset,” an elderly man hollered from the front seat.

"As for me, I massaged Ori and cassava leaves into the scalp of my wife’s sister’s child and she was cured,” another passenger retorted.

"Do you know Indian hemp can put her to sleep for two days straight?” the bus driver turned to whisper.

The only place Azuka’s condition was not an abomination was in a bus full of passengers approaching Ninth Mile, Ngwo—there was no other place. Even at Nnedi’s workplace and in the church where she shared her testimony, she always said, ‘Crisis.’

“I want to thank God for healing my sister from yet another crisis.”

Azuka’s ailment was somewhat an open secret, though she was in denial of her health status. When she managed to gain control of her senses, she quizzed her sister:

"Where is my wig? Did you say I threw my phone away? What am I doing here with you? Why are you people trying to cage me?”

Obichi and Azuka arrived safely, covered in sweat and dust. As instructed by Nnedi, they went straight to the hospital from the park. They secured a tiny corner bed near a small waste bin that smelt foul. It was as though the hospital intentionally tried to make the ward look like a pigsty that day. Obichi asked if he could go home to have a bath. Disgust laced with pity implored Nnedi to drive him home.

As he swallowed hot fufu and Onugbu soup, Nnedi asked him out of the blue if he had ever considered taking a fertility test.

"I am sure Azuka has asked you before, ehn... Don't act like you don't know what I am talking about."

Obichi stopped eating, rinsed his hands immediately, and made to leave. Nnedi pulled him back to the couch, and they stared intensely at each other for minutes before he broke the silence.

"It is not because of any stupid test that your sister is now running mad.’’

Nnedi felt the sudden urge to slap him, but she restrained herself. Her husband once told her it was men who hit women and not the other way around, so she folded her fist tightly and whispered to him.

"No, it is you who is impotent.’’

It felt as ifObichi’s ego had been yanked from him, trampled, and ground into dust. He, too, wanted to hit Nnedi, but in Igbo land, one simply never heard of a man coming to another man’s house to beat up his wife. Had Nnedi been married to his brother, he would pack her bags and throw them on the streets. He was not a direct relative, nor was he rich and reputable, in which case his in-law status would provide him space to have an opinion or act on his impulses. As far as he was concerned, Azuka was barren, and it was only normal to put pressure on her to conceive. How did that simple customary act fuel madness? It had been one year of sleeping with Azuka with no protection. No man in his family shot blanks. How could they even ask a dimkpa like him to have his penis checked? Obichi did not speak to Nnedi until it was time for them to return to where they came from.

Nnedi hoped marriage would free her from Azuka, but Obichi kept dragging her back. As usual, he notified Nnedi of their arrival, and she hid all the sharp objects in her home. She sent her children and husband to a guest house because her husband’s presence triggered Azuka, and it was best to keep the children out of the drama.

Azuka spilt every secret and called everybody out. Whenever Nnedi’s husband was in sight, her anger tripled. In the hospital, when he came to drop provisions and food, she screamed:

“Womaniser! Dirty Pig, tell my sister how many times you tried to see my panties. Does she know how you carry small small girls around town?”

Nnedi ran to cover her mouth. She squeezed her jaw tight till the nurses came to her rescue. Azuka failed to understand that marriage was a skill; as you hurt and tear, you treat your wound in silence or risk being a subject of ridicule. Was Ikenna the first? Did they not say all men cheat? Was it not in this same Enugu that a woman found out her husband was the father of their neighbour’s children? Still, she did not divorce him.

"Face your marriage, Azuka, and stop trying to taint mine!’’ Nnedi roared. She knew not to battle words with a mad person.

The Resolve

Azuka scribbled prayer requests on a small notepad. The long list included prayers paraphrased across the sheets for her husband to see a doctor.

"God, let my husband follow me to the hospital. Father, the heart of a king is in your hands. Let him consent to IVF. May my husband take the sperm test in Jesus' name.”

Azuka had gone to a gynaecologist, who examined her and confirmed that all seemed well. Nothing was damaged. He asked her to bring her husband to see a urologist for a semen analysis, but Obichi was only willing to speak to the doctor over the phone. Azuka was quick to say that Obichi did not last more than ten seconds in bed and hardly released anything. The doctor scheduled a physical appointment, which Obichi agreed to but never showed up for.

At home, he shouted at Azuka for insulting him by asking a doctor to rate his bedroom performance.

From that day, Obichi acted like Azuka was a stranger. He didn't speak to her for months. He didn't touch her either, so it was little wonder that this time Azuka travelled alone, without her senses. When her phone rang, Nnedi was just celebrating one full year without Azuka’s episodes. Azuka was found in the park, barefoot yet neatly dressed, wandering with her luggage and screaming, “My sister is doing Omugwo for my baby here,” until the bus driver took her by the hand and dialled Nnedi’s number from her emergency contacts. Nnedi came as usual and took her sister straight to the psychiatric hospital.

Nnedi knew a legion had possessed her sister when she broke off her chains and scratched the nurse’s face. It took seven strong ward maids and four doctors on duty to tie her down. This time, the madness sought to rip her apart completely—an affliction from her father's lineage, according to Obichi’s pastor. They spent an entire month in the hospital, with men and women of God trooping in to cast, bind, and declare. Azuka laughed through most of the prayers; at other times, she sat still and silent, staring at the ceiling as if her life depended on that unbroken gaze. When it became apparent to everyone that Azuka’s condition was not progressing. Nnedi decided it was time to take her sister home and manage her condition until God decided to take pity on her.

After they were discharged from the hospital, Nnedi prepared the guest room for her sister. Azuka sat quietly, with nothing to occupy her but the foam on the floor and the clothes she’d stripped from her body.

Azuka found joy in bath time, delighting in kicking over the bucket of water and flushing the soap down the drain. Nnedi dreaded bathing her but found a strange comfort in watching Azuka laugh like a child. For a moment, the madness and aloofness in Azuka’s eyes faded as they played—one sister naked and lost in herself, the other fully clothed and grounded in reality. It was a brief, bittersweet exchange—a scoop of water, a splash, the two of them together.

When the bath was over, Azuka sat naked on the cold tile, staring into the mirror. “Naked I came, naked will I return,” she murmured, her voice soft and distant.