Bouncing Baby Boy

When Obed’s grandmother ignored his cries, threw him up in the air seven times, held him upside down for minutes, and shook him vigorously during bath time, it was to make sure he did not grow up to become a young man who was afraid of heights.

Ogeli grabbed her mother’s wrapper and rolled on the rough carpet, wailing that her son be left alone. Her mother did not stop, even as Obed cried. She believed Ogeli was too young and sore to know anything about making her child fit for this unforgiving world. The throwing was the fun step, the hot pressing and moulding was the main thing. She soaked tiny face towels in water and placed them on Obed’s head, then she massaged his skull as the steam went up in the air and his little forehead reddened. She did not want Obed to grow into a young man with a coconut head or end up like his father and all the men in their lineage who became mad or useless.

Ogeli was a sixteen-year-old who fell for the whims of a fifty-year-old man. He was sweet with his words, gentle in the bedroom with her supple body and fierce in his promise of forever. Yet, the moon bore witness as he snuck out of the house and into the night, never to be seen again. That was the night Obed was conceived. In his drunken and pleasured state, he waited for Ogeli to fall asleep, and then he left. Nobody knew his whereabouts, whether he was alive or dead. He disappeared with the university education he promised her, fled with the marriage proposal and the promise to save her from the endless farm work her mother made her endure. When Ogeli’s stomach began to grow, she made peace with his absence and understood that life as she knew it was over.

Ogeli’s mother did not scold her or beat her. Instead, she watched Ogeli’s round belly grow each week, watched the innocent child kick, and blamed herself.

Ogeli gave birth at home. On the night Obed threatened to tear her stomach open, her mother put a mat on the floor, cleaned the kitchen knife, oiled her palms with anointing oil, and willed Ogeli to push. After eight hours of turmoil, Obed rolled out smiling. He received the first few slaps of his life at birth as Ogeli’s mother slapped him until the cries escaped his infant body. Then she nodded, cleared her throat, and faced Ogeli squarely as if ready to tell her all she had hesitated to say through all her brutal trimesters.

“You know this is why my husband, your father, died naked on the streets. It is why you brought home disgrace!”

“Hmm?” Ogoeli managed to say, her hips half-seated on the wooden stool, body too weak from birthing and wailing.

“His mother forgot to press his head, and I did not press yours.”

Ogeli watched her mother's hand harden on Obed’s skull.

“As for that man who left you, nobody raised him!”

“Yes, Ma.”

“But I must save my grandson.”

She massaged Obed’s head every day during bath time, and by six months, the marks on his forehead were indelible, and his head was oblong. She was going to do this until she was sure Obed’s head was fit and proper for the world, but she died when Obed began to walk and scatter things. Ogeli was left to raise her child alone.

Obed became a child she no longer wanted to carry on her hips. She wished death on him, but her mother’s throwing had toughened him. The trauma from the rigour kept him alive; he was a bouncing baby boy.

When she let him slip from her hand and land on hard concrete, he bounced back into her arms, cooing happily. When she tied him loosely on her back while she drew water and he fell into the well, his head remained above water. He could have died when she forgot him inside her cooler, filled with ice. For long minutes, Obed was freezing like the pure water sachets Ogeli reserved for her customers, but he did not die. Instead, he grew into a lanky, big-headed boy who did not take life seriously.

Ogeli quickly understood that Obed was her cross, and she had no choice but to continue carrying him.

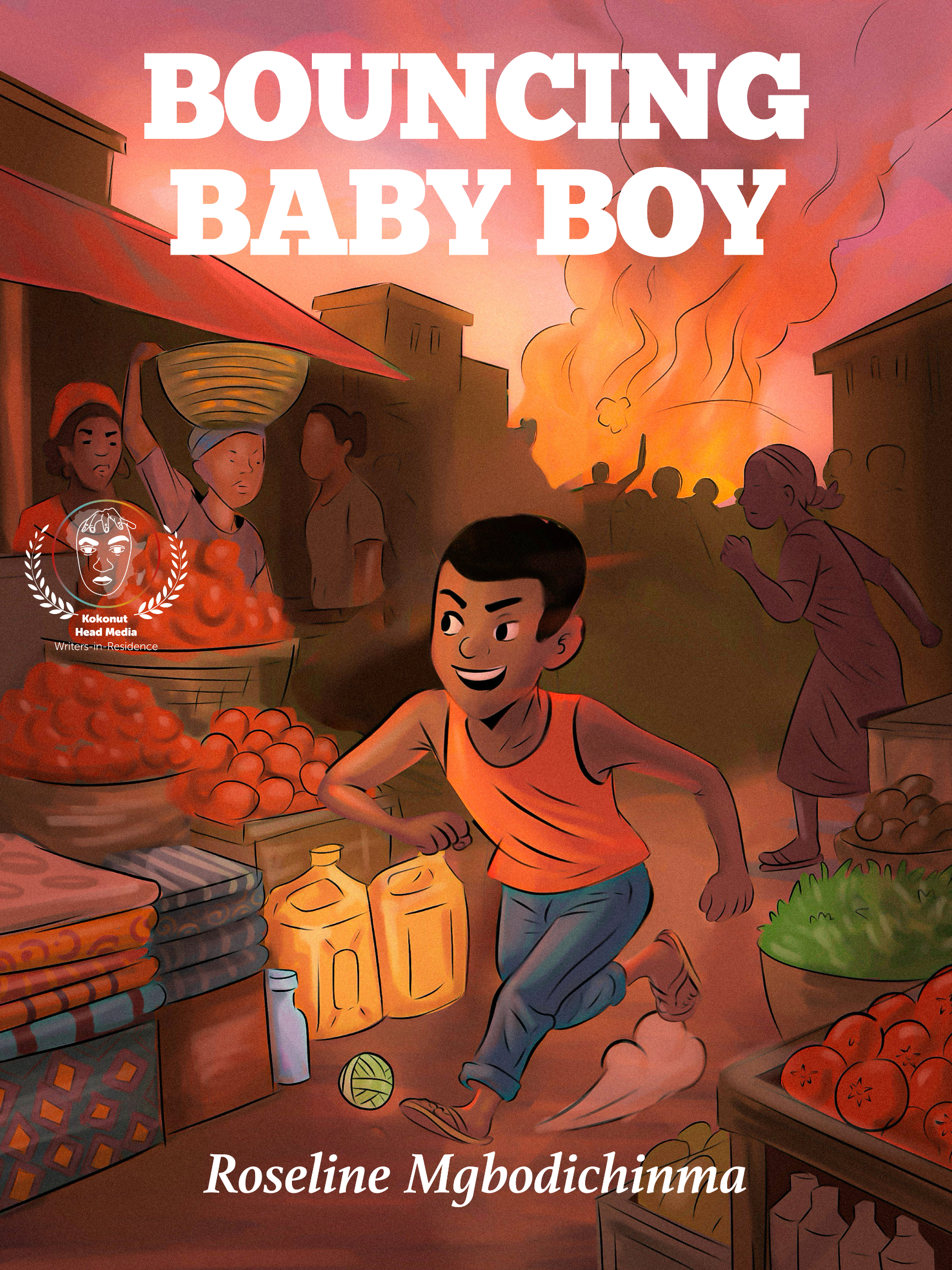

The market where Ogeli made a living was alive. It bustled with humans and non-humans, each with their agenda. Whether it be trouble, buying or selling. The roads leading to stalls and plazas were untarred, with mannequins, coolers, umbrellas and showcases so close together that they left little room to walk through. There were markers to identify each section, but they were never enough. The signpost marked as Akwa line was for various wares, but people still sold whatever they liked. Next to a heap of Okrika bale, there would be an old man selling tobacco and snuff or a woman screaming at the top of her lungs,

“Okpa di oku, buy your hot Okpa.’’

In the shoe line, people sold water drums and all sorts, navigating the market was an exercise in routine. You got lost and asked questions countlessly till you mastered the routes to your favourite customer. Obed had never gotten lost. He knew all the corners and twists and turns, he grew up sitting in Ogeli’s wheelbarrow as she wheeled around the market selling Mama put. Her stews and soups were affordable and delicious, she finished selling before it was midday. Ogeli saved enough to rent a shade in the market and focused on serving her customers, primarily labourers and hungry men who ate large wraps of Eba to make up for lifting crates of beer, mineral and heavy goods. She ensured Obed had food to eat and asked that he return home before dark to do the dishes with her. Obed was free, and so he grew into a boy who was seen under car trucks loosening people’s tyres, on top of Okadas racing away with women's wigs, beside mad people conversing, atop vegetable stands, and in the pockets of unsuspecting sellers and buyers in the market. His primary target was women. He simply loved them. How they looked, spoke, laughed. If he was not stealing from them, he was teasing girls his age and older around the market. Most of them laughed or found it annoying, some took advantage and called Obed into their shade once in a while to touch them as they liked. He was the teenager who knew his way around, the child the market raised, the one who was fast and furious, full of life on most days—near death on others.

He now liked to dance, sag, and bounce as he walked and listened to Afro beats and hip-hop blasting through the speakers in the market. His set list was on fire; there was nearly no new release he did not master. Obed wanted to take this experience to their home. He was now a big boy, so standing in front of televisions to dance and watch films in public no longer appealed to him. He wanted to be like the area boys, who hung out under car trucks and knew everything because they had big phones and televisions in their houses. Their lives looked richer than his; they were always on the move, decked in bling chains and saggy jeans. Policemen came for the boys all the time. The area boys were tax collectors and vice versa. They were the bane of all the doings in the marketplace, whether it be theft, yahoo, rape or even kidnap. The wise ones were friends with law enforcement. There was no telling who was good or bad among them, and Obed found it powerful.

Obed decided Oga Electronics was his ticket to this kind of life. On that rainy Thursday, he marked the shop and passed multiple times to make sure everyone was neck-deep in the business of buying and selling. He was used to swindling unsuspecting customers of their belongings, so this theft was supposed to be swift, and it was, but fate had an appetite for arson, and Obed was in the way.

“Burn him! Burn this boy now!”

“Pour the petrol.”

“He don thief my thing before.”

“Last week, he pass my shop and my wallet miss.’’

“Enough is enough!”

Some market sellers and passersby gathered to burn Obed alive. He was caught stealing portable DVD players from Oga Electronic’s warehouse.

Ogeli was turning garri for her hungry customers when a barrow pusher ran barefoot to her shed panting.

“Madam! Madam!’’ he said, as he fell on her cooler of Oha soup. It spilt.

“Which kind rubbish be this one now?” Ogeli was furious, her eyes watery and red. Her customers immediately grabbed the boy, ready to make him pick all the meat on the ground and pay for the pot of soup.

“Obed! Obed!”

“Ehn! Wetin do am?’’ A pot-bellied man with fufu in his mouth yelled from the corner.

“Fire! e thief! Hey! Oga Electron…’’ Ogeli did not let him finish, she ran on the ground like they were wheels. She arrived just as Obed was about to be set on fire. She begged that they burn her instead, pleading to return the stolen items tenfold.

“I go baptise your pikin with fire,” Oga Electronics fumed.

He did not need the apologies. Instead, he wanted to set an example, to let the whole market know that he could no longer be messed with. His goods had been stolen before, but not by Obed.

This was Obed’s first big steal. He unboxed the DVD player and hid it inside his oversized shirt, then boxed the carton with scraps about the same weight. It was supposed to take days before anyone realised one portable DVD was missing. The only thing Obed remembered after he got into the warehouse was that he got in, blacked out, and was now in the middle of a crowd with angry and pleading voices. The dirty slap Nwaboi, Oga Electronic’s manager, gave him made him partially alert. He could not feel his legs.

Ogeli was about to watch her son burn like the hell she swore Obed’s father went to when he left her that night. She ran around the main market screaming; many people screamed with her.

“Leave am!”

“You no go burn anybody.”

“Instead, call police.”

“Na our pikin be that.”

Ogeli pulled her weight; the area boys who swore by her palm oil stew were screaming Oga electronics and his supporters down. The married men who toasted her as she dished them Oha Soup were relentless in Oga Electronic’s face. But the real reason Obed did not exist as ash and bones that day was because in his tomfoolery, he understood balance. The same tables he stole from, he cleaned. The streets he turned into naughty corners, he swept. He fed mad people and ran errands for anyone who as little as signalled for him. In one morning, he would fix Oga Messiah’s wheelbarrow, polish Oga Emezie’s leather tyres, sort out Madam Okirika’s heap of first-grade bale, gather empty plastic bottles, and perforate their covers and fill them with water for the Mallams who sold carrots, cabbages, and green beans. It didn't surprise him when he saw them rallying behind his mother, screaming that he be left alone. Obed felt a sense of relief; his good deeds were speaking for him, and he almost felt justified in his theft. If half the market was begging for his life to be spared, then Oga Electronics was simply overreacting. Who demands a life for a DVD player?

In main market, Jungle Justice was quick. The timing between pouring petrol on a person and lighting a match was a millisecond, but in Obed’s case, the uproar stopped time. If Oga Electronics dared to pour petrol or light a match, people were ready to quench the fire before it even started. Obed was merely beaten and set free.

Ogeli cleaned his wounded body and blamed her dead mother for massaging Obed’s destiny in steam and throwing it away with the bath water. Had she not pressed his head the way she did, he would have had sense. That night, she served him food and massaged his body with hot water.

“I wash my hands off you,” She muttered.

“You want to useless your life, go ahead!’’ Obed was just happy to be alive. Unaware of what to do with this second chance, he had been dealt. He felt shame, stupid even. Big boys with swag simply do not get caught. He would spend his healing time learning how to be a sharp guy. Ogeli spent the days praying for him, asking God to change him or take both their lives. The shame and pity she had to endure at the market made her sick.

Obed's father was beginning to come alive in Obed's face. Ogeli saw his features appear on her son’s frame, witnessed Obed’s gap tooth broaden, his melanated skin deepen into a polished black— the very thing that made her throw her mother's advice in the bin and spread her legs for a fifty-year-old man.

Obed grew more precarious with age. His facial hair began to make a huge appearance and had the potential to connect; his skin glowed when he applied pomade, and he was tall. A sight for sore eyes, adored by young girls and women alike. He took advantage of his handsomeness, collected gifts and gave in to multiple advances. He was attracted to everything that moved in the body of a woman, and he chased without caution.

Ogeli begged him to break the cycle of useless men in their lineage, but he simply did not listen. He refused to stop snatching things and bending down without caution in the marketplace; everyone except Obed, believed that both spirits and men came to buy from the market. There had been rumours, some confirmed true by Ogeli and everyone who did business in main market. She had seen strange things happen as she sold food. She had witnessed with Obed how one man bought a plate of jollof from her and ate it with his mouth shut. Spoon to lips, spoon to closed teeth, the food disappeared with each spoon he took.

She told Obed about Anunti, the young woman who sold Nzu at the market entrance. Like Obed, she heard stories about spirits in main market and did not believe it. She said dead people did not have powers among the living. To prove her point, Anunti came in front of her wares, stood at ease, bent her waist, and looked between her legs. The story is that she fell to the ground almost immediately, her eyes twitched, and her mouth and ear drums were swollen shut. It was the last time she spoke or heard. With her Nzu, she drew floating men in the sand until the day she died. So if anyone’s belongings fell in the marketplace, they simply left it or squatted cautiously and picked it up, their eyes straight or above, never under, never in between, and never beneath.

Obed mocked Ezendu, the meat seller who, one day, returned from peeing in the bush without his private part. It was rumoured that he insulted an old man who was pricing down his goat meat, and the old man vowed to punish him for the disrespect. Days later, his machine, as Ezendu described, went missing. Ezendu locked his shop, and his neighbours held vigil, praying desperately to the Almighty for the return of Ezendu’s manhood. It was Brother Elijah of Die By Fire Ministries, the top distributor of tracts and New Testament Bibles, that led the 21 days prayer and fasting that he swore delivered Ezendu. On the last day of the fast, just as Brother Elijah was about to declare Ezendu a lost cause, he got a breakthrough.

“I went into the spirit realm, and I saw headless men tossing my brother’s manhood up and down.’’

“Yes, man of God!’

“I was angered in the spirit.’’

“Yes, sir!”

“That was when I summoned Angel Gabriel and Michael.’’

“Preach, sir!”

“ You witches and wizards release Ezendu’s machine in the name of the Lord,” Elijah boasted to all who gathered to listen.

“It is true! I woke up one morning, and my machine was bigger and better than before,” Ezendu cried.

It was the last time he was rude to any customer. He began selling meat on credit and advising everyone on the importance of respect and kindness.

“No dey insult customer o, no be everybody wey buy your market be human being,’’ Ezendu yelled as he saw Obed fighting a customer in his mother’s shed.

Whenever Ogeli went to buy foodstuff and left the shop for him to handle, it was utter chaos.

“Abegi! You don see where spirit dey tear kpomo? Make him give me my money whether na spirit or not!’’

“I have told you o. One day, you go see something.’’

“I no go see anything!” Obed screamed, still ruffling the customer till he paid in full.

Obed was sure he was now untouchable. It had been months since he was nearly burnt alive, and his sudden audacity was due to the passage of time. He moved without regard and joined the ruthless market tax force, which overcharged market sellers and buyers with parking and gate fees. Obed spent many nights outside Ogeli’s small house. In his free time, he boldly made advances and catcalled women with his tax collector friends. They threw dirt on women and howled insults at them.

“You no even fine.”

“Fine girl, many pimples.”

“This your skirt too short, we go soon pull am down.”

“Las las, na me go marry you.”

Obed was also a sweet talker who knew how to spin the girls who fell for him. First, it was Obiageli who sold meat at the butcher stand. Ogeli always wondered why her kilo of meat differed from Obed’s. When she went to buy meat, the size was moderate. When Obed went, five kilos looked like ten. It was when she caught Obed’s hands inside Obiageli’s skirt at the back of her shed that she understood why. She did not stop them. She simply took her basin of utensils, looked at Obed the way one looked at a helpless situation and scurried away. Obed was great with his hands; AdaNgozi, the market tailor, could testify. She was twice his age but thrived off the attention Obed gave her. His eyes lingered on her slightly unbuttoned blouse, and he winked at her when he passed her shop. She knew Obed belonged to the streets but was grateful for the piece of him she could ravish. AdaNgozi only did quick fixes, could not make a dress from start to finish, but could mend almost any clothing. A small stitch here and there for customers in need. Area boys came in for button changes, pocket tacking, and hemming. Obed’s zipper always needed a change, and she was happy to do it quickly and on her knees while Obed’s hands danced inside her blouse. There was nearly no impressionable woman in the main market that Obed had not touched, one way or another. On many occasions, sales girls yapped with him all day and forgot to balance their accounts at the close of work. Madam Okirika warned him to leave her sales girl alone, to stop taking her to dark corners, and giving her free food,

“Obed, it will not end well for you. Leave woman alone!” she warned.

“Tomorrow I dey come collect my tax, and if you no get am, we go burn all this your second-hand cloth,’’ Obed hissed and went to play under the truck with his boys. They gathered under a spoilt truck just beside the vegetable market.

From under that truck, Obed saw a woman approaching. She was tall, dark-skinned, and dressed in shorts and a see-through blouse. Her gold jewellery adorned her ankles, wrists, and ears. She clinked with each step she took.

“Omo, see fine girl now,” one of the boys said, mouth open and tongue out.

“No approach am o, this one na my own,” Obed shouted, pressing his mouth shut.

“Psst, hey you, fine girl, stop there!” the boy yelled, running to meet her.

“Guy, stop this madness, na me get this one.”

The girl saw Obed and the boy running towards her, but she did not care. She did not mind them yelling and catcalling her so long as nobody touched her. Years ago, when she was alive and came to buy fabric for her tailoring business, she got lost, and tax boys took advantage of her. They told her the fabric shop was inside the market and that they would show her the way and give her a good price. They, instead, took her into a deserted shed and stripped her naked. They took turns touching her body and laughing. They made her touch them in all the places they desired. This was her second coming, and she roamed the earth in peace. She was not a troublesome spirit like the ones who stole Ezendu’s manhood or rendered Anunti speechless. She only came for those who came for her. Her visit to the market was always swift. She got fabric and jewellery and left almost immediately.

“Fine girl, Blackie, my colour,” Obed continued to chant.

The boy had left him to chase and focused on roughing another girl. Obed had her to himself, and he was going to collect her number and touch her at all costs. He came behind, matching her steps even as she increased them.

“Why are you running, eh, Sisi?’’

She did not speak or look at him.

“I dey follow you talk, you dey do shakara.”

Obed was now too close for comfort.

“You no go leave am alone,” a pepper seller said as they walked past her stall.

“E consign you?” he yelled in return.

Obed was tired of the fun of following her around. She was just moving, not saying a word, and not shooing him away, just moving. Obed was irritated by her unflinching silence, how she made him look so insignificant, like a housefly hovering around dead corpse. He was not used to this kind of ignorance.

“You no dey hear all the thing I dey shout since,’’ Obed screamed, grabbing her by the left arm to turn her towards him. What happened next was unprecedented.

She stopped and looked Obed in the eye, a darting, hypnotising glare that made him lose sensation on his two feet. His whole world spun, and although the market grounds were concrete, it felt like sinking sand, like the ground was pulling him in. Obed tried to scream, but his mouth was paralysed with inaudible sounds. Nobody came to his aid because, on a physical level, nothing was happening. What the roadside sellers could see from where they sat was Obed and a fine lady looking at each other, in what felt like two minutes, but a lifespan for Obed. He couldn’t think properly. This woman’s stare paralysed him from his forehead to his toes. He felt almost dying, almost buried.

Obed previously lived for the thrill because this fast-paced life, laced with unruliness, gave him the adrenaline to outrun the nut in his chest. That thing inside him that longed for a normal functional family life, the one where he was never sent back from school or sent to the market, the one where his father and mother were present. For the first time, Obed thought about Ogeli, how she truly felt about his bad behaviour, what losing him would do to her, and how he was indeed his father’s son: brash, inconsiderate, wayward, always in close sheaves with death. He felt shame. Was it truly a blood thing to die and disappear through mysterious circumstances? Obed swore at that moment that if he got out alive, he would become a monk and never touch or look a woman in the eye, even his mother. He had started seeing pockets of light and blinks of darkness. He knew for a fact that his end was near if no one intervened. In Obed’s head, even if he wound up in hell, they would be thrilled to know how glorious his exit was, that he, a big-headed boy in his teens, stood transfixed as a girl he catcalled, in what felt like an eternity, glared at him, took seven steps backwards, pointed straight at his chest, waved her hands at him in circular motions. He began to tumble, roll, roll, and bounce on tables of goods and wares, his body jittering till every buyer and seller, old and young, took to their heels. He would tell the devil that he heard his mother calling out his name, but there was no life to answer. He would say that Ogeli did not stop running since she was told that her son was flying in the air like a wounded cockroach in the middle of Awka Market. She ran, as always, to rescue him, but this time, she met him bloodied, bruised, and battered in a trench just beside the deep market sewage dump. She hummed her tears, unable to do anything but groan. Ogoeli mounted Obed on her tired back and began running, running to the nearby health centre, hoping that her only son Obed had not breathed his last.