You Must be Mine

“Your husband is cheating on you,” she announced.

The silence in the room was deafening.

“Did you hear me? I said Chima is cheating on you,” Mrs Alamba repeated.

I heard her the first time, but I was trying to digest the information with a gulp of fruit juice, letting it water my parched throat before replying.

She took a swig from her glass and I felt like taking it from her hands and pouring it on her cheap Ankara gown for ruining my peaceful afternoon. I knew she didn’t give me this information because she was looking out for me or wanted me to hold my husband accountable for his infidelity. She was one of those women who wished for my life: plush rugs, ornate furniture, live-in help and crisp naira notes.

She was a member of the Nwunye Odogwu Association in Lagos, a group of women who came to events in monster trucks with latching bags of naira notes that reflected the wealthy status of their husbands. Over-priced jewellery, hot-pepper-red lipstick, and nostrils that were perpetually hung in the air while they judged others for wearing old-season Louis Vuitton and 2008 Toyota Camry.

“They say she is a very fine girl. A modern-day slay mama on Instagram. And you know Chima not only has money but he is fine as well. Someone saw him leaving the apartment he bought for her in Lekki,” she went on.

I still couldn’t respond.

“They say she is thirty years old. My question is, why can’t she look for her own husband? Why should she play second fiddle to another woman’s husband?”

I cleared my throat while adjusting my dress in an effort to inform her that her stay was no longer welcome.

“I just said, let me come and tell you as my fellow woman, and I hope God blesses you with children. You know they say, children bring a couple closer.”

I glared at her, hoping the remainder of her orange juice would choke her as she swallowed it.

I knew her visit wasn’t of pure interest but a means to rub it in my face that she would rather have a faithful, broke man than a rich man who whistled at any beautiful girl in a short skirt. Proof that life wasn’t balanced and no one could have it all. At least God was fair, and she couldn’t complain. Her children were all enrolled in the State Primary School, and her husband came home to her every night.

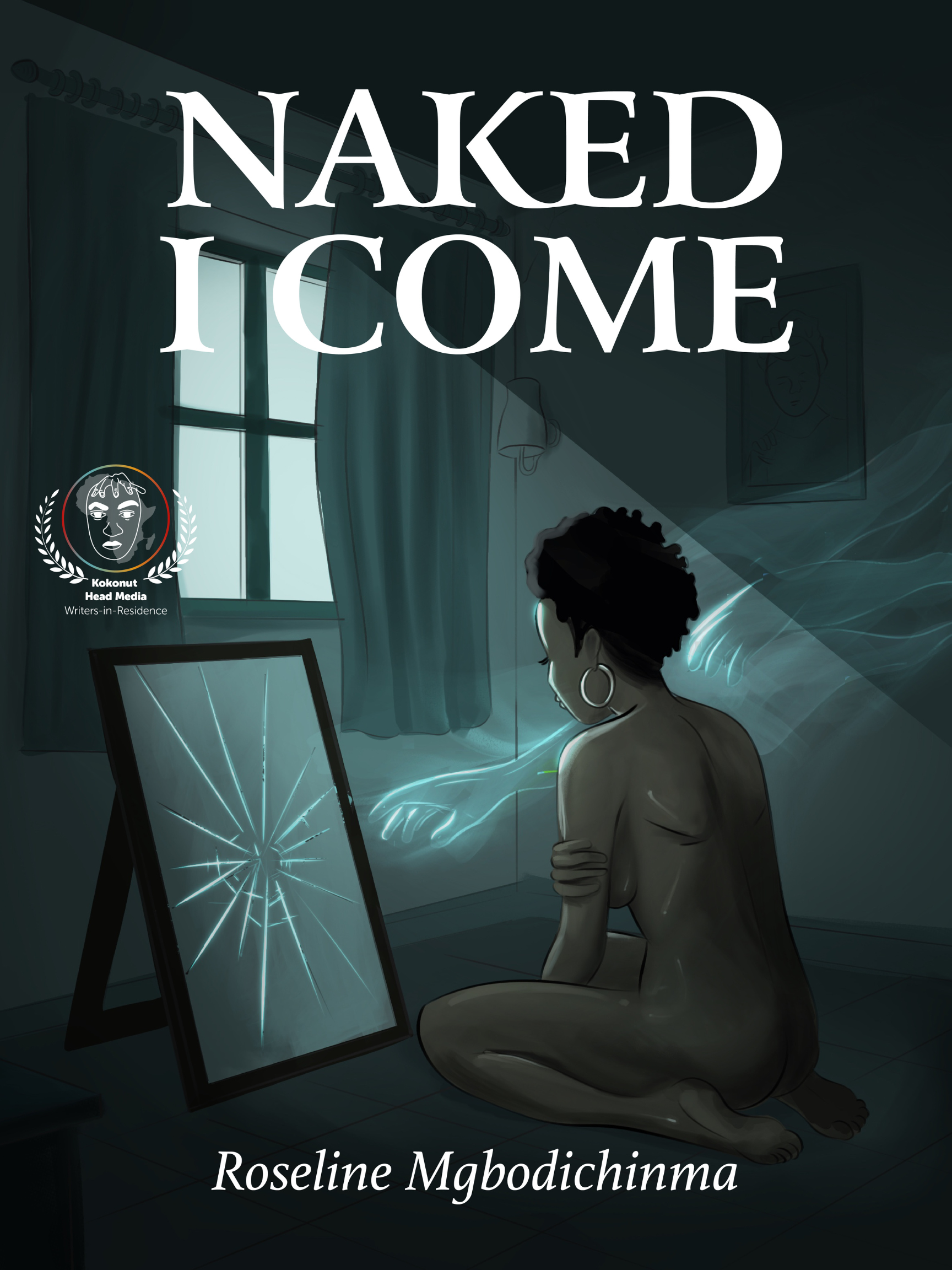

When the gateman shut the gate after her, I walked upstairs, lifting one heavy foot after the other, my shoulders weighed down by the news I just heard. I sat in front of the vanity mirror where tubes of lotion, retinol, and body oils were arranged, staring at my brown face. I rekindled memories of how he raised my skirt on the table and thrust into me a few nights ago. My fingernails tore into his back as he pumped his seed into me, willing a child into this empty body, this womb that seemed too caustic to let a child grow there. I imagined him now, in the arms of another woman, feeling his warmth and begging him not to stop.

I hadn’t been innocent all my life. I had been the ambitious, big-eyed secretary to a big man, desperate to claw my way to his heart by tearing his family apart because his wife couldn’t give him a child. I promised to rock his house with the cries of a baby. From the moment I saw him as I walked into his office that interview day, the sexual tension in the air was thick, as viscous as soup made with ogiri. This was a man torn from the pages of Igbo fantasy novels, the type that went to war with masculine bodies wielding cutlasses that glistened in the sun. His face was clear-cut like a stone statue, and his body shimmered like burnished brown sand. I kept forgetting the words I had rehearsed, trying to keep up with his voice that dripped with finesse and candour.

“What are your strengths?” he quizzed.

“I can do anything you want,” came from my lips.

“Sir, I need this job,” I said without thinking, and he smiled, amused by my boldness.

I got the job with my unusual interview and became the secretary who wore short skirts and belts that made my thin waist look slimmer. I massaged oil onto my cleavage until it shone, and threw my legs out while swinging my hips from side to side.

My boss was every woman’s dream. He bought me snacks from Mr Biggs and took me out of state with him on official assignments. During one of these visits, I got closer to him and listened as he talked about the need for an heir.

“We are in Nigeria,” he said one night as we sat down in a resort, enjoying the nightlife, the dancers, and munching on suya. “I need a child, a male heir to bear my last name. I am a hardworking, rich man, so who will I leave all this for in the end? I can’t even talk when my friends are talking. When they talk about school and the issues their children are giving them, I just sit back and drink my beer. Some have even asked if my manhood is working.”

His pain was real and his fears were unmasked in his words. He sighed and shook his head as sadness enveloped his eyes. I saw a man burdened by societal expectations as people questioned his virility. I saw an opportunity to make him happy. Life was business, the ability to discover problems and offer solutions.

Things got heated as I took him to his room and offered to put him to bed. Our eyes locked, and our lips followed suit. It was more exciting than any relationship I had ever been in. The rush of eating from fruit that wasn’t yours and stealing from a garden you didn’t plant was what made it different; you gobbled up the food before anyone caught you. This love was reckless, destructive, and razing down everything in our path, including the books on his table as he lay me down and raised my skirt.

His wife was collateral damage as she had no idea that while she was gulping down olive oil recommended by pastors to unblock her fallopian tubes and fasting till her rib cages were visible, her husband was getting oiled by his secretary, who had promised to give him the son he desired.

It went on for months before she found out. I still remember the terrified look on her face as she tore the door open and saw me, legs spread open on the executive table, as he moved his waist in motion. Her head tie fell to her forehead, just above her eyes as her lips shivered without the right words to say. The food flask and napkins she had packed daintily with love poured from her hands, and she left the office a heartbroken woman who never quite recovered. I never forgot her last scream before she dashed out like there were mad dogs on her trail.

That was almost five years ago, and now, I have stepped into the shoes I badly wanted to be in. Not only did they pinch, but my toes were squeezed and swollen. In my land, not having an heir for a rich man like my husband was a travesty. People whispered about you as you walked by and likened you to harmattan, dry and dusty. They told you to give way for another young, virile woman who could give your husband the sons you couldn’t, just like the woman before you.

My mother-in-law no longer smiled when she visited and boldly called me a Dimkpa, a man like my husband, because “of what use was a woman whose womb was a desert ground, thirsty, parched, and incapable of growing anything?” Her wrinkled feet were cracked from going from one prophet to another, seeking a solution for this useless fig tree, just as Jesus had described it.

Each one told her a different story: one said I was in a coven where we pounded our young in a mortar, fed on them, and gulped their blood, another called me an ashewo because of the way I entered my husband’s heart from the back door and a lot of hot, rusty hangers had done my womb no good that it couldn’t hold anything.

“Leave my son, Karashika!” she spat, the veins on her neck visible and threatening to burst open.

I opened the cupboard in the room, clearing a mound of clothes to reveal a box I had tucked in the back. The box contained two dolls I had been given that night. The dolls were wooden, a male and female wrapped together with a red cloth signifying the bond between me and my husband. I had gone back to my village in Obowo, to a strong witch doctor my mother introduced me to, to help me fortify myself and gain favour before I travelled to the city for employment. The witch doctor came to the night market. In our land, it is believed that the night market is the time spirits and humans come to haggle. It buzzed all night and disappeared at the brink of dawn.

The woman saw me wandering and tapped my hand. Then, I followed her to the hut at the market entrance, where tongues of fire surrounded the centre as she sat. Her face didn’t form any lines when she smiled, and I wondered how many years she had lived. She poured some cowries on the ground and stared at the shape that formed on the ground.

“What have you come for this time?” she asked.

“I want love. I want a man to love me”

While drawing lines in the soil, she asked for his name and date of birth. After drawing the fifth line and bundling it together, she looked up at me, concerned.

“This man you speak of is already tied to another, and the land's gods approve of their union. Why do you seek to destroy instead of building yours?”

I hadn’t expected these questions; I only wanted her to wave her hands and will him to me.

“He is the one I want, and I will do anything to have him,” I replied.

“Why do you want a love you don’t deserve?”

“He is my soulmate, and we are supposed to be together.” I was desperate.

She chuckled and threw the cowries again.

“It is not written that you are supposed to be together. In all my years of work, one thing you cannot buy with juju is love. Pray to the gods that they send the one meant for you. You cannot build your happiness on another woman’s misery; the four elements of the universe will work against you”

I didn’t listen. I was ready to do anything and pay any amount for her to make my dreams come true.

“This cannot keep a man. You might fool him and make him see things that are not there, tricking his mind to see you as the woman he has only ever loved, but one day, those scales will fall off, and he will see you for who you really are. What is not yours will never be yours. This highway is dangerous, and it only leads to a river. Do not let it sink you.”

Her words flew into one ear and rushed out from the other one, carried by the wind. She obliged me and gave me some sugar cubes with a potion made from purified water, white powder, and lemon peels. I was to pour them into his morning coffee after reciting some words she told me. I did as she asked and watched him sip the hot coffee with the love potion Mama called Sweetie. She advised me to pour one spoonful of Sweetie into his coffee for seven days in the morning.

By the seventh day, I got him down on his knees, and it wasn’t to say a prayer. I let down my panties, inserted the sugar cubes, and listened to the clinking of my waist beads as they bounced on my body just as the witch doctor instructed. I lay on the table as he raised my hair and whispered into my ears, promising to send his wife packing.

I got the man and the home I wanted, but I couldn’t give him what he wanted, and he was already losing patience. I had to go back to Obowo to ask why I couldn’t get what my husband desired.

He came home that evening; the smell of Silk Oud announced his arrival as the door slammed shut. I came out to welcome him, a glass of wine in hand, leaning on the wall and watching him take off his shoes and unbutton his well-starched white shirt.

“Welcome, my love.”

I dropped the glass and reached out to help him remove his shirt. We walked into the sitting room, and he sank into the cushion, rubbing his head.

“I had a busy day at work. He sighed.

Of course, I thought to myself, you had a busy day with your side piece in Lekki.

When it was time to eat, I watched him tear his chicken apart, waiting to see if he would show any sign of guilt. Instead, he was straight-faced, chewing on the bones and gulping fresh juice.

“How was your day at work?” I asked, breaking through the cold silence.

“It was fine. I had a meeting with a few investors, and we are working on a pitch to draw them in. So far, I love what they have presented to me.”

I knew he would never say where and in whose arms he spent the lunch break. I set the table, scooped the steaming egusi on the dainty ceramic plates and hot eba on the other plate and watched him roll the mound and drop it into his mouth. The only sound came from the noise his mouth made as he rolled the eba and swallowed.

“I hope you weren’t stressed today?” I questioned further, hoping he would say something and let it slip that his car had been spotted at the gate of the home of his mistress. But he just mumbled some inaudible words and went on eating. Afterwards, he retired to his room and dozed off.

This was how it continued for the next few weeks. We barely talked except when I requested money or told him about the trip to the gynaecologist’s office, showing him test results that showed healthy ovaries and clear tubes. He never followed me for these appointments because an African man was never considered sterile; it had to be the fault of the woman somehow. I thought it was the childlessness that drove a wedge between us and wore over our marriage like a dark cloud, but I discovered he was soliciting the services of other women.

I knew what I had to do. It was a fruitless affair running after the mistress or threatening her. It would only make him more bold and desperate. I packed a bag, kissed him goodbye, and travelled to Obowo, to the night market, where it had all begun.

The night market was buzzing with traders, trays of plantains and pepper, baskets laden with fruits. I walked among the humans and spirits, searching for a dark figure stooped with white hair adorning her head like a crown. Someone tapped me, and I turned. It was her. She smiled and waved me to the hut on the market's outskirts.

“You returned, just like I knew you would.”

I was stunned. “How do you know?”

“I read the signs, child. You were never meant to marry that man.”

“I want a child.” I didn’t waste time stating the reason I was there.

The woman chuckled, fondling some beads. “The world doesn’t work that way, Zara.”

“How?”

“Remember the last question I asked you when you came here?”

I ransacked my mind to recall.

“This is a marketplace. Abana is the god who rules Afor Ibizi, and we buy and sell. I sold you the life you wanted at a price.”

“What price?” My heart sank deep into my stomach.

“No one knows the ways of the gods. I am just a medium. I didn’t even know till I saw you tonight.”

“Speak,” I ordered, agitated by her ominous words.

She threw different colours of beads on the ground and stared at them for a long time.

“The gods took Chima’s vitality. He cannot get you pregnant.”

I stood up like I had been stung by a viper.

“You can get pregnant, but not just through him.”

I heard her, but it took time for the words to sink in.

“But his first wife couldn’t give him a child!”

“It wasn’t in her destiny to give him children, but you can,” she replied simply.

The information spun in my head. I slumped to the ground, staring at the dancing flames as the market bustled outside.

“How long do you intend to do this?” she queried.

I didn’t have an answer.

“You must go. It is almost dawn.”

I picked up my bag and stumbled, catching the first glance of the orange sun tinting the landscape. Back home, I walked straight to a bar where no one knew me and ordered a glass of whatever was trending. This place became my refuge in the days that followed. When I returned home, I sat for hours in bed, eating little.

“You won’t be able to find your way back home if you keep drinking like that,” someone interjected three nights into my routine.

I turned to see if it was someone I knew. Instead, I was met with a tall stranger who was strikingly handsome and aware of his attractiveness. He took the glass from me.

”Who are you?” I asked.

“My name is Dayo, and you are a beautiful woman who shouldn’t drink alone at a bar.”

I smiled in response. It had been a long time since I had heard those words. I knew his game, and I wanted to play it, too. I would have ignored him on a normal day, but I needed all the company that evening, so I let him linger. He bought me a drink, and I leaned on him as he directed me to my car. That signified the start of a partnership.

I came to the bar often to sit and chat with him, tossing my ring into the dresser. It was on one of those days I decided to let him hold my hand and when he kissed me, I forgot about everyone else in the background. I pulled his hand and led him to my car and watched him pull down his trousers. Maybe he could give me what I wanted. How long do you intend to do this? The woman’s question rang in my head. For as long as I needed to secure my place in Chima’s life.

I lay on my back and begged him to make me feel like a woman. When we finished, I breathed slowly, willing my legs to stop shaking as I told him I wanted to see him again. We met again and again until I fell sick, sat in the toilet, and dipped the test strip in the amber urine. The two lines ran down reassuringly. There was life growing in me. I rubbed my belly and smiled.

My husband’s eyes lit up when I told him. He carried me up and swung me around in the air for a long time. He rubbed my back when I threw everything I ate in the sink, prepared pepper soup, and kept me up-to-date with my doctor’s appointment, ensuring I swallowed my vitamins and folic acid tablets. People congratulated us, and even his mother sent her shallow, insincere well wishes, and I accepted all in good stride.

We both went for regular scans, where we watched the love in me grow. I made friends with the jovial, chubby Nurse Barbara, who booked my appointments and ensured I saw the doctor immediately. I came after I pressed crisp naira notes in her hand. Most nurses, with their tired and worn cornrows, wouldn’t give you attention if you didn’t butter their palms.

I woke up one morning in the seventh month of pregnancy in excruciating pain. On getting to the hospital, the doctor announced that I had a high-risk pregnancy and my baby would be in distress if I didn’t put to bed immediately because her head was in an awkward position.

“But I did everything I was supposed to do,” I blurted out. “I took my drugs, did the right exercises and rested well. How did this happen?”

The doctor didn’t answer. Instead, he motioned the nurses to prepare me for surgery.

I was wheeled into the labour ward on a hot Sunday afternoon, praying to God to spare my child, but God didn’t play any games. My baby was born sticky, raw, and fragile. She had to be kept in an incubator. The doctor reeled off terms like ‘asthma’, ‘arrhythmia’, and ‘paralysis’. I knew it would take a miracle for our child to survive.

My husband was the most disappointed. In rage, he hit his hands on the wall and screamed, “Why?! " until people who had come into the room to investigate the cause of the commotion led him away.

I watched a tear escape his eye, and for the first time, I saw my husband cry. I had failed him, once again.

I stood at the window of the incubatory room, watching my baby take slow, weak breaths. Nurse Barbara came up to me and whispered in my ear, consoling me and assuring me that I wouldn’t leave the hospital without a baby.

“How?” I asked.

“Don’t you believe in miracles?” she replied with a mischievous smirk.

It wasn’t my destiny to give my husband children; it was time to make peace with it. A few weeks later, I left the hospital with a baby that Nurse Barbara placed in my hands after I gifted her a bag filled with crisp naira notes. She had taken a baby and given it to me. I would tell my husband that somehow, our baby had survived, our miracle baby.

I knew he would believe me and he would love me again.