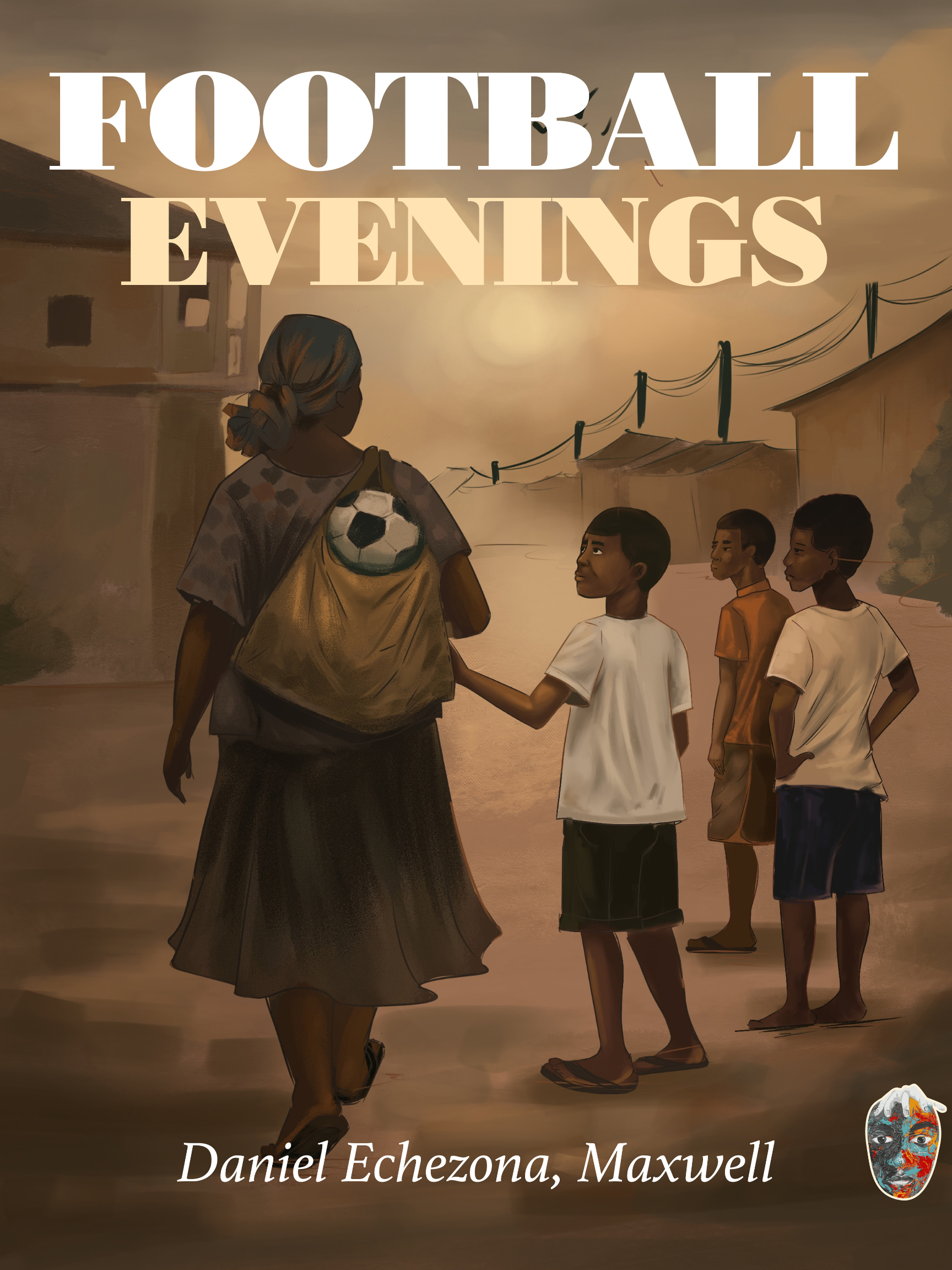

Football Evenings

If you come to our street in the evenings, you will find all the young boys in our street at our football field of scanty grass. It really does not matter how rough school has been for the day, because we will always be happy as long as we have our ball, legs and the field. There is barely anything better than playing football, shirtless and sweating, throwing swear words at the mother of an idiot who refused to pass the ball, or a bastard who missed a goal. Sometimes, when NEPA decides to give us light just in time to watch live matches on TV, we sit with hearts calcified by sportsmanship, screaming at a missed goal or celebrating an actual one. But most of all, we watch the feet of the players— the skill in their movements, the algorithm of the accurate passes, the timing between trapping the ball and launching the fierce shot.

And then in the evenings, in our field of scanty grass, we try to replicate the moves we have seen. Our field is the vast compound of Number 17, on which stands a single uncompleted two-storey building. They say the owner of the compound is in jail abroad, no one knows for sure. But it has been deserted for as long as I can remember and grass has begun to dominate the compound; the boys before us played their evening ball there, before they all grew and went off to secondary schools and universities. It is here, in this field too, that we become our own Mourinho and Neymar and Ronaldinho, hoping that some day a big club will come sign us to play big matches in England and China. Madu holds this dream so close to his chest, although in truth he is not in any way the best player among us.

Sometimes we think it is stupid of Madu to hold so many future ambitions with equal tenacity. He believes he can be everything at once. He talks about being a cardiologist with the same fire of passion that he dreams of being in Ronaldo’s Manchester team. He wants to be a lawyer too, even though Emenike has told him once that he cannot be a doctor and a lawyer at the same time. It must be Madu's mother who feeds him all these big-big dreams; she seriously wants her child to be a big man, maybe a doctor or engineer, but not a footballer. So whenever she is at home, she locks Madu indoors and makes him read and read even though the boy just wants to follow us and play. Sometimes, I feel this is what they tell us in church, that the most painful thing about hell fire is not being allowed to do what you want to do. Just like being forced to read when you actually want to play.

This evening, we are complete. Not all the boys are here, because some of them now take extra lessons after school, for their upcoming exams; but at least we are enough to have two teams of six boys on each side. For us, that is a complete team; and a complete field is marked by twelve boys, six shirtless and the other six wearing their shirts. Our alternative model for a jersey.

Landlady sits on the low fence in front of our compound as we play today. Beside her is Emenike, the carpenter whose workshop is at the end of the street. Everyone knows that Emenike has no shame— last week, he had stripped himself of all clothes and walked round the street for a bet of fifty thousand naira. I wonder what Landlady does with him. It is people like him that give Landlady a bad name; and make everyone spread gossip and rumours about her. Some people say that she killed her husband to win a court case, others say she is an ashawo— I once fought my classmate who said he saw Landlady at Tonybiz, the popular brothel for prostitutes. It makes me sad when I hear these things, because I like her. And she likes me. And she lets me have the change after running errands for her.

Sometimes, I wish I can tell her to stop talking with Emenike, or allowing him into her room at night. But in our street, you cannot advise your elders, and I am sure Landlady is older than my daddy. She celebrated her fifty-ninth birthday last year. My brother says that what Emenike and Landlady do is just adult business, and our own business is to just play football. He never listens when I tell him the things I hear about Landlady; he says that if I don't stop worrying about what doesn't concern me, then I will lose my ability to dribble and score goals during football. It sounds more like a threat to me each time, because the goals and the continuous buzz it generates are what fill my heart whenever I send a ball past the goalkeeper into the post.

Like now, in between dribbling an opponent and kicking the ball into the post, I think I catch a slight sight of Landlady leaning on Emenike's shoulder. My heart burns as I register their smiles.

“Goal!!!” My teammates erupt with joy, some giving me high-five and some giving me the kind of hugs we call Brotherly. And me, I feel like a little Lionel Messi.

The celebration is short-lived, and we continue the game. The other team launches a fierce attack with a vehement focus at scoring a goal— and instead of calculated moves, they shoot recklessly towards the direction of our post. The compound where we play has no fence nor gates, and if you stand in its middle you can get the full view of the street, of our house on the other side of the street, and Landlady seated with Emenike on the low concrete fence.

One of the boys, who is perhaps the most vexed at his team’s inability to score a goal, gives a radical kick at the ball with so much force that the ball races over our not-so-high post and ends up hitting Landlady's face.

None of us stands to process the look that immediately washes across Landlady's face. We all run, each person as fast as his legs can take him, into Number 18 where the girls are playing their game-start. From the distance, through the star-shaped holes on the fence on Number 18, we see Emenike wiping Landlady's face with a handkerchief and patting her back. The girls have now stopped their game, startled by the speed with which we ran into the compound, and are also watching with us as Landlady picks up our ball from the ground and walks into her compound.

“Aaarrgghh!!!” Almost all the boys shout in unison.

We know our ball is gone. Forever. We are never going to get it back. One by one, we walk, defeated, to the cleared left end of Number 18 where the Catholic Charismatic members often hold their seminars. We sit on the empty wooden benches stacked in the corner. For a while, we say nothing, each boy perhaps wondering how a ball was with us this minute and forever gone the next. We know we have to think up something, fast, before it gets late and we disperse to our separate homes for the rest of the night.

When the first person does speak, he asks how we can possibly get a new ball. Getting back the seized one is obviously out of the question— Landlady has seized seven of our balls for different reasons in the past and we never got back any.

“We could contribute to get a new one,” one of the boys says.

“But it will take a long time before each of us save up our own share of the money,” Madu says.

The last time we had to buy a new ball, he was five days late with his contribution. His mother rarely gives him any money, and he has to explain in detail what he wants to use any single kobo for.

But in truth, there is no other option. If we must get a new ball, we would have to pool money together for it, although some of the boys insisted that Odera, who had kicked the ball at Landlady, should replace it. The group splits, some titled towards Odera in support, others maintain that he should bear the full blame and replace the ball.

“Dubem, can't you go and beg Landlady? You know she likes you.” My brother says, his voice rising above the cacophony of dissenting voices. Everyone hears him and turns towards me— a distinct kind of hope suddenly present in their eyes. It is not the kind of hope I can shatter. Not when it is my brother who brought up the request. So after gentle nudgings by my friends, and the reminder which my brother whispered into my ear— if the ball is returned, then the both of us won't have to think of a lie to tell Mummy and get our own contribution, I agree to try my luck.

Rising, slapping dust from the back of our shorts, we all walk in near-unison to Numbers 15, our compound. At our gate, a girl runs up to us and tells Madu that his mother has returned from work. Madu waves us goodbye, wishes us luck and runs home with the little girl. Madu lives at Number 21, on our own side of the street, just three houses away from ours.

I knock at Landlady’s door until my knuckles begin to ache. My friends perch at a distance in the compound and urge me on. The only response I get is the muffled sounds coming from inside the room, and Emenike’s unmistakable voice asking for rubber and music and handkerchief, all at the same time.

With smashed hopes, my friends head back to their compounds, my brother and I sit out in front of our room and wait for our parents. Tomorrow, there will be no football. And next tomorrow, too. Until we get the money for a brand new Bladder size 11.

*

“I heard you were knocking at my door the other day,” Landlady begins when she calls me into her room three days later.

I feel my hands shaking, and that if I speak my words will make no sense. I have never been this close to her as to take in details of her facial features— particularly the mole on her right cheek.

I say nothing. I nod.

“You cannot talk?” she asks.

Of course, I can talk. I can tell her that the last time someone told my father that I entered her room, I had to swear by God and Virgin Mary that it was a lie. My father's whip can make one swear by the devil. I can tell her that my mother has sworn to cut off my legs if I am seen anywhere around Landlady’s apartment. I can tell her that if we don't get this ball back, my friends will easily put together their own money for the ball, but there's no way I'll get any money from Daddy soon.

“You wanted your ball, abi?” She asks now, cutting my thoughts short.

Before I even say yes, she goes into her inner room, one shielded with a curtain, and brings a big, empty sac.

“Hold this bag and follow me.” She hands the sac to me and steps out of the room. I walk closely behind her till we get to her packing store at the corner of the compound and she unlocks it. The store was dimly lit, with squiggled paintings on its wall like the handiwork of some impish child in love with ribald graffiti. It smells of disuse, of something antediluvian, a kind of room that could count how many times it holds humans within its walls.

In this storeroom, there are over a dozen balls stacked in a corner, and I wonder how many times boys have had to mourn their happiness, how many curses have followed each seized ball into Landlady's life. When she says I should pack all the balls and return to their owners, I know I should say Thank You, but I only nod. I want to tell her the things in my mind. I want to tell her that most of these balls do not even remember their owners, that I have only come for just one. I smile in compensation for the words I am unable to say, and begin gathering what I have come for.

*

This night, Daddy locks me in his bedroom and whips me with his long koboko, not listening to my pleas or explanations. He screams loud words into my ears in heavy baritone. That thing I am looking for in that woman's house, he says, I will find it. And when I do, he will not be there to save me. I wonder what he means, but the pain of the flogging outweighs my ability to make any meaning out of his words of indictment. When he finally lets me leave his room, exhausted by the marathon of landing countless strokes of the leather whip all over my body, he orders my mother not to give me dinner

It is my brother who steals some garri from the kitchen for me.

Again, someone has told on me to my parents, and my brother swears to find out the person. He will teach the person to mind his business, whether adult or child. The night stretches interminably, and the pain from the whipping increases with each second.

“Sorry,” my brother says every two minutes or so, asking if the flogging still hurts.

“No.” I say each time, flinching as he brings his hand close to me.

“Then stop crying nau,” he says, reaching for a Vaseline tube to apply some on the welts on my skin.

But I am not crying just because the livid welts from the flogging still hurt. I am crying because last month, Landlady fixed our leaking roof immediately I complained to her; she had called an electrician to fix our light the day after I told her about the electricity issue in our room. She made sure to enforce daily cleaning of the toilet in our wing just after I told her how messy the place used to be.

I am crying because my parents were quick to say Thank you to her, but are now boiling in anger because I'd gone to her room today, for something as plain as retrieving a ball for me and my friends. I am crying because I know that tomorrow morning, my mother will greet Landlady with the most cheerful smile, but will come into our room, make us hold our ears and warn us not to go anywhere close to ‘that woman’. Because tomorrow, the boys will gather again under the evening sun to play football, the laughter and arguments will rise again. And no one amongst them will know that this night, I am trying to find a good position to sleep.